DECLASSIFIED

S E C R E T

Narrative by:

Captain V. R. Viewig

USNUSS GAMBIER BAY

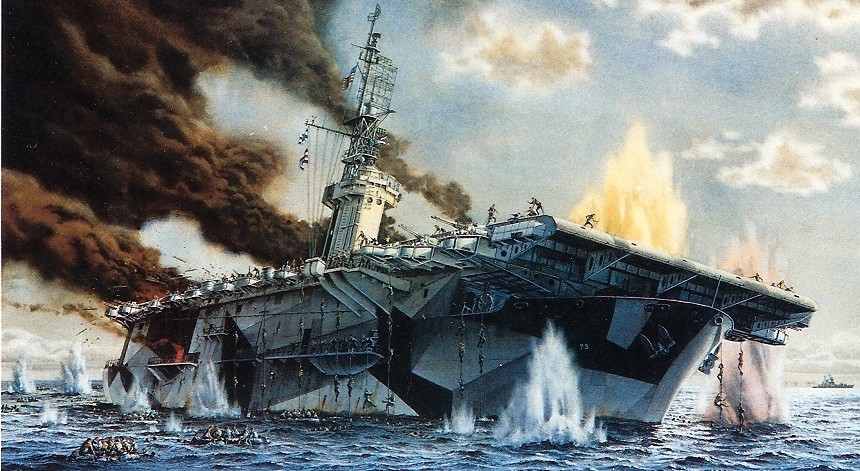

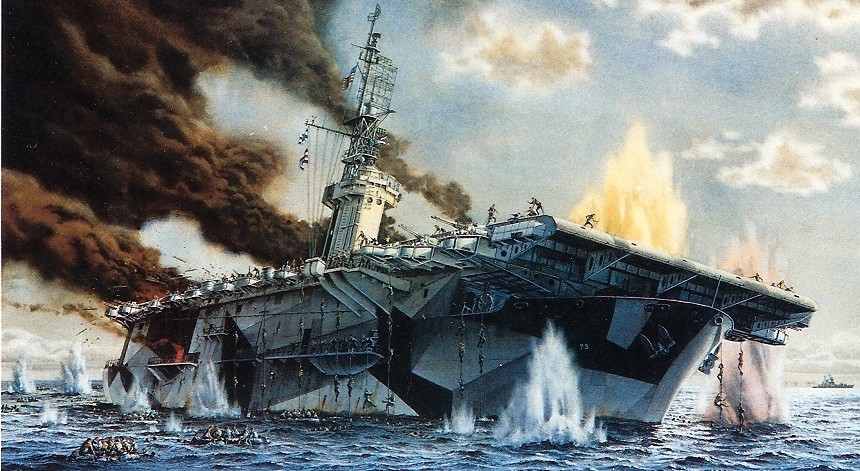

Second Battle of the Philippines

With considerable detail, the captain of the CVE GAMBIER BAY tells here how that ship was lost in the Battle off Samar on 25 October 1944. He also tells of his experiences in the water and his rescue. This narrative also includes a brief account of the GAMBIER BAY’s earlier activities.

File No. 315

Copy No. _____ of three copies

Recorded: 18 December 1944

Rough Transcript: Ariancia, 20 Dec. 1944

Smooth transcript: Scherrf, 15 Nov. 1945

Captain Wright:

This is in the Office of Naval Records and Library on December 18, 1944. This morning we have with us Captain W. V. R. Viewig of the GAMBIER BAY. The next voice that you hear will be that of Captain Viewig.

Captain Viewig:

I assumed command of the USS GAMBIER BAY, which is a Kaiser class CVE,

On the 19th of August 1944. At that time the ship was anchored in Segond Channel, Espiritu Santo, New Hebrides Island. Shortly after assuming command the ship proceeded in company with other carriers to Tulagi where it provisioned and prepared for participation in the seizure or Palau.

The GAMBIER BAY’S part in the Palau operation was to furnish aircraft for direct air support of the troops seizing the island and this operation was conducted without any enemy air or surface attacks reaching the GAMBIER BAY. Our planes did destroy many of the ground installations and in return received some AA fire which damaged some of our planes. But, as a matter of general interest, we lost not a single plane during the entire operation either from enemy action or operationally.

On completion of this operation we joined a force under Admiral Blandy which was to seize the Atoll of Ulithi. This operation is probably well known. It was extremely uneventful in that no Jap opposition was encountered and the island was taken over without any losses whatsoever.

Upon completion of the Ulithi operation the GAMBIER BAY, with the KITKUN BAY and WHITE PLAINS, proceeded towards Hollandia with a force returning troops from the Palau operation. We gave this force air protection enroute.

After arrival at Hollandia we proceeded to Manus where we commenced preparation for the Philippine operation. The GAMBIER BAY left Manus on 8 October, with Task Group 78.2 under the command of Rear Admiral Fechteler. The GAMBIER BAY was the only carrier with this force for several days and provided principally antisubmarine protection and, in addition, furnished some utility services in the form or towing planes for ships antiaircraft gunnery training. We also took advantage of this time to exercise our fighters at fighter direction and to give our fighters a chance to do some dive bombing for practice on a sled towed by the GAMBIER BAY.

About the 11th or 12th of October, I do not recall the exact date, we joined with the KITKUN BAY and with the remainder of Task Force 73 which had come from Hollandia. These two carriers, the KITKUN BAY and the GAMBIER BAY, under the direct command of Rear Admiral Ofstie, proceeded toward Leyte rendering antisubmarine and Combat Air Patrol protection for the task force, that is Task Force 78.

This force was scheduled to land two divisions in the northern part of Leyte. Upon arrival in the general vicinity of our assigned operating area to the eastward of Samar on the evening of the 19th of October, we left the task force and joined a group, Task Group 77.4, under the command or Rear Admiral T. L. Sprague. Our first assignment was actually in Task Unit 77.4.3 under Rear Admiral C. A. F. Sprague.

Commencing with the morning of the 20th, which was the day the landings on Leyte were made and continuing until the 20th and even to the 25th, we were occupied in rendering direct air support to the landing operations and occupational movements of troops on the island of Leyte. We provided Combat the Air Patrol, antisubmarine patrol for vessels in the transport area off Leyte. In addition we provided the same services for ourselves. Our principal job, however, was to launch air strikes against enemy ground positions which we did throughout this period from the 20th to the 24th.

The period 20 to 23 October, was quite uneventful in that we receive no air attacks, and life was quite peaceful aboard ship. The 24th was routine with the exception of the fact that our early morning Combat Air Patrol managed to shoot down seven enemy planes over Leyte. However during the day and into the evening there was something ominous about the reports that were coming in about the movements of enemy ships in the eastern Philippines. It was quite obvious to me from our plots of positions of enemy forces, which were obtained from radio intercepts, that something was stirring and that the Japs were assembling a considerable force of ships including battleships and cruisers. Because of this situation, although our job was not to attack ships of this category, we realized we might perhaps be called upon to divert from our primary mission of supporting the ground operations. I had a conference the evening of the 24th, involving one executive officer, the air officer, our operations officer, the squadron commander of the squadron embarked, who was Lieutenant Commander Huxtable, commanding VC Squadron Ten.

We also had the air ordnance officer at this conference.

I was particularly concerned to make sure that we were ready in case we were called upon to launch a torpedo attack. Among other things I made sure that all our pilots were recently briefed in enemy ship identification and also in the technique of torpedo dropping. They had no recent training or experience in this and I was particularly anxious to make sure that they were at least as well briefed as could be and knew the latest thoughts and techniques pertaining to torpedo dropping. In addition, quite naturally, I made sure that our ordnance gang was fully prepared to load torpedoes on short notice.

At about 2:30 in the morning I was awakened by our communications watch officer who brought me a message indicating that the Battle of Surigao Strait was taking place. Immediately upon receipt of this message and realizing that we might have to help out, I ordered all un-obligated planes loaded with torpedoes.

To clear up what I mean by un-obligated planes: we had a routine schedule to meet for the following day and our forenoon demands for torpedo planes were such as to leave only four of a total of 11 Avengers on board without a prospective chore assigned. The torpedo loading was commenced immediately after issue of this order. Two planes were loaded with torpedoes and two more torpedoes were placed in the fully ready condition and could have been loaded in a few more minutes.

At 0500 in the morning we launched eight fighters to take up routine station over Leyte as Combat Air Patrol for the protection of our ground troops and transports. This flight was launched by catapult in complete darkness except for the lights shown by our screening vessels. There was nothing particularly eventful about this operation worthy of note.

At about 0620, as I recall it, the sun came up. It gives you an idea of how dark it was when our planes were launched. At 063O we had been at general quarters, of course, since about 0430 at the time we started the warming up of planes for the 0500 launch. At about 0630 the officer in tactical command, Rear Admiral C. A. F. Sprague sent a signal by TBS to the effect that commanding officers might secure from general quarters at discretion. I secured from general quarters and went to condition 3 but remained on the bridge as did the navigator who was working up his morning position.

At about O645 things commenced to happen. He intercepted a rather frantic voice transmission from a plane we believed was in an adjacent task unit, Task Unit 77.4.2. The gist of the massage was that the Jap fleet was there somewhere about 40 miles from his home station. We didn’t have to wait long to get additional information. One of our own task unit’s antisubmarine patrol planes reported the presence to the northwestern, distance about 25 miles, of a Japanese fleet consisting of four battleships, eight cruisers and 13 destroyers. Almost simultaneously there reached me on the bridge a report from the radar room, and there was visible in the PPI on the bridge a force which could be nothing but enemy since we knew of no one that should be in a position 25 miles to the northwest of us. The radar plot confirmed the report from our antisubmarine patrol.

To make certain of the situation required no great amount of thought since about that time major caliber salvos commenced falling in the center of our formation. Just prior to this contact we had been on a northernly course, which as I recall it, was 040. Only a few minutes before the contact we had reversed our course and were headed in a generally southernly direction. Immediately this contact was made and identified as enemy. The officer in tactical command ordered a course change which brought us generally to the east, and was near enough to the wind to permit launching.

Without waiting for instructions I commenced launching all planes on deck since I was under immediate threat of losing everything due to a shell hit on deck and setting the planes on fire. I managed to launch all ten remaining fighters on deck and in addition, the seven torpedo planes that were on deck. Unfortunately the torpedo planes were not fully loaded with bombs or torpedoes due to the situation.

You see we had our planes loaded for missions involving direct support of shore troops and the loading for that was a combination of some planes with a hundred pound bombs and others with 500 pound general purpose bombs. Our next scheduled flight, scheduled for 1000, was an antisubmarine patrol and we were caught in the process of shifting bombs and hence some of our planes had the depth bombs in them that they would be used at 10 o’clock, some of them had nothing in them and others still had the general purpose bombs in them. Our planes, however, did much good in the air as you will find out later. They probably did delay utter catastrophe to the whole task unit.

As soon as I had completed launching the planes on deck, I started bringing up the planes from below which were the four torpedo planes which were not obligated for morning strike missions. Other planes that were brought up from the hanger deck were gassed since it was routine doctrine to keep all planes below the flight deck de-bombed and degassed for the safety of the ship.

By this time the officer in tactical command had changed course in small increments towards the south and when my planes were brought up on deck we had very little relative wind movement over the deck. According to the tables we didn’t have enough wind to launch a fully loaded and fully fueled torpedo plane. The first torpedo plane to be launched with a torpedo in it was accordingly launched with only 35 gallons of gasoline in it. This plane subsequently launched a torpedo successfully against the enemy and then, of course, was lost.

The first torpedo plane, notwithstanding the fact that it didn’t have enough wind over the deck, went of all right and I permitted the fully loading of the second one with gasoline. This was launched with a full gasoline load and torpedo in it and also took part in making an attack on the enemy.

The remaining two planes were gassed fully. One of them was brought up on deck and later on jettisoned. We had changed course a little more to the south which brought the wind almost directly astern of us and there was only a five knot relative wind over the deck and I know that was certain death for the crew to catapult it and hence I pulled the crew out of the plane and catapulted the plane without a crew just as a means of jettisoning it since we were by that time threatened with hits. Salvos were falling pretty close.

During the period from about 0710 to about 0730 the enemy main body was pretty well concentrated astern of us generally to the north of us. Our destroyers made an attack at this time. All or our ships made smoke, Our planes in the air made attacks, repeated attacks, many of them without bombs. About this tine a rain squall intervened and that result of all these things in combination was such as to bring about a lull in the firing from the enemy force. And also a change in their relative position.

When we came out of this rain squall at about 0830 as near as I can tell the situation was essentially this: we were still in a good formation, that is, the carriers were. As a matter of interest, there were six carriers in the formation, all equally spaced on a circle 5,000 yards in diameter, The ships were stationed in the following order, clockwise, the ST. LO was due north of the center of the circle. Other ships were in clockwise rotation separated by 60 degrees in the following order, KALININ BAY, GAMBIER BAY, KITKUN BAY, WHITE PLAINS, and FANSHAW BAY. The latter ship contained the O.T.C. and at that time was the guide.

All our destroyers, all our screen consisting of three 2,100 ton destroyers and four DE’s had already left their screening station which had been a circle outside of this inner circle of CVE’s. They had left and made their attack so that at about this time as we came out or the ruin squall, carriers were still in this circular formation. Our destroyers and destroyer-escorts were gone away from the formation; engaged in smoke-laying operations, torpedo attacks, and gun fire.

The enemy’s main body, that is, the battleships, were essentially about ten miles to the north of us. A division of cruisers of either three or four in number, probably of the TONE class, had gained station about 15 or 16,000 yards to the northeast of the formation. The wind was generally from the northeast. As a result the GAMBIER BAY and the KALININ BAY were on the exposed windward flank of the formation where our own smoke provided very little coverage between us and these cruisers to the northeast. It did offer more protection to the other ships of the formation. And the destroyer smoke and their attacks momentarily, at least, suppressed the fire from the main enemy battleship body to the north, directly to the north of us.

These cruisers then to the northeast were in an excellent position and without opposition to pour in a rather heavy fire upon the GAMBIER BAY and the KITKUN BAY which they proceeded to do without delay. However, their fire was somewhat inaccurate, not very fast, salvos were about a minute or a minute and a half apart and they did not fire a particularly large salvo, they fired four gun salvos. Apparently the Tone class were firing alternately the first two turrets and then the second two turrets rather than firing an eight-gun salvo. Why that was, I don’t know. The pattern of this four—gun salvo was rather small. Their spotting was rather methodical and enabled us to dodge salvos.

I maneuvered the ship alternately from one side of the base course to another as I saw that a salvo was about due to hit. One could observe that the salvos would hit some distance away and gradually creep up closer and from the spacing on the water could tell that the next one would be on if we did nothing. We would invariably turn into the direction from which the salvos were creeping and sure enough the next salvo would land right in the water where we would have been, if we hadn’t turned. The next few salvos would creep across to the other side and gradually creep back and would repeat the operation. This process lasted for, believe it or not, a half hour during which the enemy was closing constantly.

When the range was finally reduced to about 10,000 yards, we weren’t quite so lucky and we took a hit through the flight deck, followed almost immediately by a most unfortunate piece of damage which I believe was caused by a salvo which fell just short of the port side of the ship and the shell probably exploded very near the plates outside of the forward engine room. We had a hole in our port engine room as a result or this hit or, near miss which permitted rapid flooding of the engine room and made it necessary to secure. With the loss of this one engine my speed was dropped from full speed of 19 1/2 knots to about 11 knots. Of course, I dropped astern of the formation quite rapidly and the range closed at an alarming speed.

The Japs really poured it in then and we were being hit with practically every salvo, at least one shot in each salvo did damage to the ship, although there were still occasional wild salvos. During the period from this first hit, which was around 8:10 in the morning, until we sank, which was about 9:10 in the morning, we were being hit probably every other minute. The hits that went through the upper structure did very little damage since the shells did not explode inside the ship. However, those shells which hit either just short or below the water line did explode and the result was that in very short order I had a flooded after engine room. I had to secure which left the ship helpless in the water and without any power to provide water pressure.

Up to this time we had managed to keep our fires, started by the shell hits, suppressed, but when we lost water pressure, every hit was a small fire, which soon developed into a larger one. The one remaining plane on the hanger deck was hit and caught fire, the gasoline in it caught fire. I do not think that the torpedo, torpex – loaded, exploded, but I believe the gas burned at a high rate, approaching explosion.

At about 0850 with the ship helpless in the water and with this division of cruisers passing close by and other ships of the main formation passing close by on the other side and being fired at from all sides, I ordered the ship abandoned. As we were abandoning ship the enemy ships in various directions were still firing. As a matter of fact, as the ship rolled over at about 0904, as I recall it, somewhere in there, a few minutes before she completely disappeared, there was a cruiser about 2,000 yards away still pumping it in and also still missing.

After we sank, the enemy ships that had been firing on us went about their business and pursued the remainder of our formation and disappeared from sight. However, perhaps the most alarming thing of the whole operation, from my point of view, was the fact that very shortly alter we sank I observed a large Japanese ship dead in the water about three miles to the eastward. We were pretty low in the water hanging on to a life raft bouncing up and down and not feeling too well. I’m not so positive of the identification as to say that I’m entirely right. I believe it was a battle- ship of either the KONGO or FUSO class since the pagoda type structure would indicate such was the case. Personally, I did not see the stacks but an officer trained in identification is quite certain in his own mind that it was a KONGO class battleship since it had two stacks.

At any rate this ship remained dead in the water until about sunset at which time it gradually picked up steerage way to change course to the north and disappeared from sight. This ship was at all times attended by a destroyer, a two stack destroyer, which during the early hours would seem to disappear and reappear and we couldn’t quite figure out what it was doing, whether it was picking up people or what. Once the ship got underway just before sunset, this destroyer continued to circle the apparently damaged battleship.

The following day, the 26th, thank God, there was no enemy ship insight. It is a matter of conjecture with me what happened to it. We were not picked up as you can gather on the following day, in fact, towards night fall we could see the beech which we believed was Samar. We expected to be sent that way by the wind and currents. Midnight the 27th passed by without our being picked up and shortly thereafter we sighted ships which we hoped were friendly. We waited until we were entirely certain of their identity at which time I fired a Very star and received a prompt reply. Some time between midnight and daybreak in the morning the bulk of our survivors were picked up.

Personally the small group I had with me consisting of about 150 men gathered into a cluster of rafts was picked up about 4:30 in the morning, thereby making our cruise in the water of about two days‘ duration.

To go back a little bit, may I say once I got clear of the ship and was personally safe, my first thought was to assemble all the rafts into one large group. This I proceeded to do and had collected about 150 people when I observed this battleship. At that time I thought I had better quit that process since it did attract attention and the last thing in the world we wanted to do was to be captured, so I ordered the assembly of rafts discontinued and we all just laid low quietly in the water and tried to show nothing that would flash or attract attention.

As a matter of interest as to how I personally managed to get off the ship: I remained on the bridge until everyone was off the bridge and the navigator who had the deck, and I remained up there and we saw that abandoning ship process was continuing successfully and people were getting off and at that time I directed the navigator to leave the bridge and look out for himself, which he proceeded to do by clambering down the life lines which led from the open bridge.

I myself wished to make doubly sure that everyone was clear and proceeded down through the island structure. However, by this time, apparently there was a terrific fire, probably caused by the one remaining plane on the hanger deck. Smoke and hot gasses were pouring up through the island structure and I found myself in a rather embarrassing position in that I couldn’t go back up on account of the smoke which was really climbing up through that area. And about that time another salvo went through the bridge structure which urged my departure. I continued, however, down to the flight deck and when I reached there, the gasses were so hot and black that I couldn’t see.

I managed to feel my way aft along the island structure hoping to reach the cat walk and perhaps get aft and below that way. However, instead of walking down the ladder into the cat walk gracefully, I fell into it, not being able to see and I couldn’t make out for certain where I was, in fact, I was so confused at that moment that I thought I might have gone further aft than I had and had fallen into a stack, so hot and so black were the gasses. However, I reached up instinctively.

At this time I was probably prompted solely by instincts of self-preservation and grabbed a hold of the upper edge of that I was in and pulled myself up and over and started falling and a few seconds, perhaps a fraction or a second later, I broken to clear air with water beneath me. I fell about 40 feet and hit the water with quite a smack.

I had on me at that time my helmet and my pistol which seemed to help very little since it gave me a good jab in the ribs and my helmet, being secured at the time almost choked me as I hit the water. However, I came up quite rapidly and the cold water seemed to revive me very quickly and I felt in perfectly good health except for my somewhat crippled right side which prevented my using my right arm very much.

However, I think under these circumstances the instinct of self-preservation will take care of some rather astounding damage and I had no trouble in making my way clear of the ship once I started thinking and realized I had to swim aft instead of away from the ship. I had gone over the starboard side and the ship was drifting rapidly to starboard and being set down upon me and I couldn’t swim away from it at all but swam aft.

About the time I got aft to the ship, aft to the starboard quarter, another salvo went through the ship and at that time the ship was almost ready to roll over. The port side was in the water to the extent where the hanger deck was under water. I got about 100 yards off the port quarter at which time the ship very slowly rolled over to port and very slowly sank, and there was no serious detonation.

I did take the precaution to get my rear end out of the water by putting a board under it and lying on my back but apparently that was unnecessary since there was no major explosion. I’ve told you what I did from there on in after the ship sank. I tried to assemble life rafts until I thought it imprudent on account of the nearness of enemy vessels.

In all this account I hope you will recall that all records were lost and that I am stating things purely from memory. Times may be slightly in error, but I don’t think seriously so.

As a matter of overall interest in the battle, may I say that I entered this battle with absolutely no knowledge of the fact that the enemy we en-countered had gone through San Bernardino Strait the night before. Information to this effect, if obtained by higher authority, had not been transmitted to this ship. I think that’s about all I have to say.

Capt. Wright:

Thank you very much, Captain Viewig

END

* * *

P

CVE-73

A16-3/A9-J

USS GAMBIER BAY (CVE-73)

C/O Fleet Post Office

San Francisco, California

27 November 1944

From: Executive Officer.

To: Commanding Officer.

Subject: Report of Battle.

Reference; (a) Article 948, U. S. Navy Regulation

1. The general conduct of the ships company during the action, while abandoning ship and in the rafts, was in general excellent. The crew acted in a calm and well-disciplined manner throughout. The abandoning of the ship was accomplished rapidly and without any indication of panic.

2. No cases deserving of censure were reported. Although no examples of heroism or extraordinary bravery were disclosed, the following men are recommended for letters of commendation for their ceaseless and unselfish efforts in aiding and comforting the wounded, both on the rafts and in rescue vessels: GALLAHER, Harold V., PhM1/1c, Ray, Allen F. HA1/c, and TRIBBETT, Raymond A. RM1/c.

3. At the time of writing there are 133 officers and men missing or killed in action. The following parts of the ship were those where the greatest number of casualties occurred: (a) gallery deck, port side, in the vicinity of the Forward 40mm battery; (b) gallery deck, port aide, in the vicinity of the Communication Office; (c) the hanger deck. The latter being the scene of the greatest number of deaths, because of the concentration of personnel in the process of abandoning ship.

4. The following are suggestions for the improvement of abandoning ship equipment:

(a) The use of bungs in water breakers was proven impractical. Those that withstood the shock of being dropped in the water were soon knocked out of the casks when handled in the rafts. A spigot positively fixed to the breaker is required.

(b) The buoyant material of the floater nets is made of laminated sections which pinch the occupants of the nets, causing spots subject to infection and aggravating salt water sores. The edges are so sharp as to cause, at the least, extreme discomfort. This buoyant materiel should be made in single pieces or the laminated sections should be securely bound, and all edges should have a large radius bevel.

(c) All water, food and first aid packet containers, should have external handles or loops, so that they may be towed by the rafts. When kept in the raft: they are a constant inconvenience and annoyance, particularly if wounded are aboard.

(d) Kapok life Jackets, are by far the best of the various types of personnel floating aide for the following reasons: (e) not subject to vital damage by shrapnel; (b) its shape gives more support in the water;

(e) it helps keep the body warm. Of course, Kapok jackets are too bulky to be worn at all times about the ship, particularly during action. However it should be the practice to have one of them for each man at or near his battle station for use when abandoning ship.

R.R. Ballinger

*

PART II

“PLAY BY PLAY“ NARRATIVE”

October 25, 1944

O415 Manned all Flight Quarter Stations.

O430 Manned all General Quarter Stations.

0457 Commenced launching VF (FM-2 Fighters) by Catapult.

0505 Completed launching 8 VF (FM-2 Fighters).

0616 Sunrise.

0635 Received TBS message from OTC “Set Condition 3 at discretion of Commanding Officer”.

0637 Secured from General Quarters. Set Condition 3. Captain and Navigator on bridge.

0640 Anti-Aircraft fire observed to the Northwest.

0643 Intercepted an almost unintelligible excited VHF transmission from in ASP plane from T.U. 77.4.2 to its base to the effect that the Japanese fleet was sighted 30 miles from base. (T.U. 77.4.2 was operating 10 miles south of our position at the time.)

0644 A local ASP plane reported an enemy force consisting of 4 BB’s, 8 CA’s and/or CL‘s and 4 DD’s.

0645 A large unidentified surface force indication appeared on SG Radar bearing 300° (T) distance 23 1/2 miles.

0645 Sounded General Quarters.

0646 OTC gave signal by TBS ”Execute upon receipt 9 turn”, (making new course 130°) and ”speed 16″. Executed signal except, on orders from the Captain, engine room was directed to make maximum speed.

0647 OTC signaled by TBS “Make maximum speed possible.”

0647 All General Quarters stations were manned.

0648 The OTC commenced passing information concerning the contacts and made urgent requests for immediate assistance to C.T.G. 77.4. and Commander Support Aircraft Central Philippines. These transmissions were in voice on 2096 kilocycles Inter Commander Support Aircraft circuit. This circuit was loaded with this type of traffic throughout the engagement. Enemy “Chatter” was heard intermittently on this circuit but apparently no attempt was made to effectively Jam it.

0650 OTC gave signal over TBS “090 turn.”

0652 Order given to jettison three (3) remaining napalm bombs located on No. 5 sponson.

0654 Gun flashes observed on horizon to the Northwest and large caliber salvo splashes were seen falling near the ships on the northern side of the formation. (enemy’s initial firing range established an approximately 35,0O0 yards.)

0655 All planes on the flight deck (7 TBM-1C and 10 FM-2) turning up ready for launching.

0657 Commenced launching planes.

0705 Completed launching all planes on flight deck. (This left 4 TBM-1C aboard – all on hanger deck).

O708 Brought 1 TBM-1C up the forward elevator.

0709 OTC signaled by TBS “All carriers lunch all aircraft”.

0710 Launched 1 TBM (loaded with 1 torpedo). Destroyer screen deployed making smoke to cover the CVE group.

0715 – 0730 Foul weather between own task Unit and closing enemy forces momentarily checked fire and only a few salvo splashes were observed in the formation during this period.

0723 Changed course on TBS signal to the south.

0730 Picked up on SG radar two or three vessel: bearing 170° (T) distance 19 miles.

O730 Enemy force, at least six separate tracks on DRT, making approaches from 270° around to about 060°.

0731 Advance cruiser unit moving around northeast flank. Estimated speed of this unit 30 knots. Weather partially cleared between own and parts of enemy force.

0731 Salvos splashing intermittently near GAMBIER BAY, WHITE PLAINS and FANSHAW BAY under concentrated fire.

0732 Destroyer screen ordered by OTC to deliver a torpedo attack.

0733 One TBM loaded with torpedo brought up from hangar deck on forward elevator.

0734 Commenced pumping aviation gasoline to gas the plane now on the flight deck.

0738 Completed gassing and purged the gasoline systems. (Pumped inert gas in risers to all filling stations.)

0740 OTC gave TBS order to “open fire with the “pea shooters” when range is clear.

0741 Commenced firing 5″ gun at enemy cruiser 17,000 yards on port quarter. (Approximately 30 rounds expended before gun was put out of commission by near miss and three (3) hits were observed on target: one hit on forward turret, one on fantail and one on bridge. Shells were fired with fuses on safe and damage to enemy is considered slight.)

0745 Launched one TBM, enemy salvos straddling the ship.

0755-0810 Salvos fell near the ship shortly after fire was opened with the 5” gun. During this period the ship was maneuvered to avoid salvos.

0746 Changed course to 210 (T) (on this course there was not enough wind across the deck to catapult a loaded TBM).

0750 Jettisoned one TBM by catapult. (This left only 1 plane – a TBM – aboard which was on the hanger deck near the forward elevator.)

0750 Three unidentified ships sighted on horizon dead ahead of formation. Sent effective major war vessel challenge on 24” searchlight. All three ships responded immediately with correct reply. On the strength of this identification (too far away to be identified by sight), on order from the Captain, the Signal Officer sent “BT WE ARE UNDER ATTACK BT K”. The center vessel “dashed” for each word and “rogered” for the message. (It was thought by some that these ships proved to be enemy and closed and opened fire.

0800 Changed course on was signal to 200°(T).

0805 Changed course on TBS signal to 210°(T).

0810 First hit, after end of flight deck starboard side near Batt II. Fires started on flight and hangar deck – personnel casualties small.

0815 Changed course on TBS signal to 240°(T).

O820 Hit in forward (port) engine room below waterline.

0821 Two portable electric submersible pumps placed in operation. Bilge pumps started.

0825 The Captain informed OTC by TBS that ship had been hit hard and had lost one engine.

0825 Engine room flooded to burner level. Boilers secured.

0826 All loads shifted to after generators and engine room.

0827 Forward engine roan secured. Slowed to 11 knots, dropping astern and out of formation.

O837 Lost steering control forward probably as result of ruptured liquid lines by shell fragments from hit in or near the island structure.

O840 Radars went out of commission.

0840 After engine room hit – 8″ shell entered skin of ship pierced No. 3 boiler and probably lodged in the lower part of generating tubes.

0842 Water poured rapidly into after engine room from the sea. Bilge pump section taken in after engine room.

0843 All boilers secured on order of the Engineering Officer.

0845 Ship dead in water. Ordered all classified material jettisoned.

0850 Gave order to “abandon ship”. (The ship was in a sinking condition surrounded by three enemy cruisers firing at point blank range.)

0855 The Navigator, who, as Officer of the Deck, had remained with the Captain on the open bridge until then, was directed to abandon ship and did so via the starboard bridge life lines just as another salvo pierced the island structure.

0858 The Captain attempted to reach the interior of the ship via interior island structure ladder but was driven onto the flight deck then aft over the starboard side by hot block toxic smoke.

0907 Ship capsized to port.

0911 Last sign of ship disappeared from surface of the eater.

0930 – 1230 During this period the majority of the survivors assembled into seven or eight separate groups. They lashed life rafts and floater nets together and collected sections of flight deck planking and any other floating debris with sufficient positive buoyancy to support those for whom there was no room on or aboard the rafts.

At least three attacks before noon by groups of four to six TBM’s each with escorting FM’s were observed on enemy ships to the Northeast, East and Southeast. Inaccurate bursts of anti-aircraft fire was seen as these attacks were being made. With the exception of a large vessel with a destroyer standing by to the southeast, none of the enemy ships were seen by the survivors in the water. this particular ship has been definitely called a Kongo battleship by a few and not so positively identified as a heavy cruiser by others.

1300 Dive bombing attack (6-8 SBD’s and F6F’s) approached at 10 – 12000 feet altitude from the northeast, made a complete circle around to the south, and took departure to the northwest. (Presumably in pursuit of the retiring Japanese force). As this fight circled around our group intermittent but effective bursts of AA tire were observed apparently from the ship or ships damaged and dead in the water and by their escorts.

1800 Large Enemy vessel (Kongo Class BB) with a destroyer nearby in sight during the forenoon still visible and observed on a northerly heading at very slow speed (if underway at all), by some of the survivors. (Note: This ship was not seen the next morning and some survivors believe it was scuttled during the night as heavy explosions were heard during the night).

October 26, 1944.

0900 1 TBM and 1 FM, together, passed five (5) miles to the east at altitude 6000 feet. Red and green Very stars were fired and dye markers thrown in the water. The planes apparently saw none of these and continued on their northerly course.

0945 Same two planes observed at 0900 returning five (5) miles to the west on a southerly course. All attempts to attract attention were to no avail.

From time to time several groups of survivors sighted each other and closed within hailing distance.

Two men were lost to sharks during the late morning and early afternoon. Lt. Budeurs, who was lost, had taken off his trousers and was wearing only white skivvy pants when he was bitten in the buttox and died a few minutes later and was buried at sea.

1200 All groups were about equally spaced along either aide of a line bearing 260°-080°, 35-45 miles from the center of the coastline of Samar.

2230 T.G. 78.12 (2 PC’s and 5 LCI’s) sighted Very stars fired by various groups of survivors. (Note: This task group had been dispatched from Leyte Gulf to locate and rescue the survivors of the ships sunk in this engagement. They had arrived at the reported position of sinking, which was about 15 miles southeast of the estimated actual position, at 0800 26 October. This group made continual sweeps north and south with the search line running east and west until they sighted the Very stars indicated above.)

October 27, 1944

0000-0430. Ships of T.G. 78.12 picked up approximately 700 survivors from the GAMBIER BAY 15-20 miles east of Samar.

0700-1000 Search was continued by C.T.G. 78.12 and survivors from the HOEL, JOHNSTON, and ROBERTS were rescued.

1000 T.G. 78.1.2 departed for LEYTE GULF. (Note: There were no aircraft observed by either the survivors or the rescue vessels offering any effective assistance in the rescue operations.)

1200 T.G. 78.12 under attack by three Japanese dive-bombers which scored near misses on ships of the unit but did no damage.

COMMUNICATIONS

RADIO:

A11 radios functioned satisfactorily with the exception of intermittent interference noted on 2096 (ICSA – Voice) caused by atmospheric conditions. Japanese chatter was heard sporadically on this circuit and also on 37.6 (IFD) just prior to contact and during the engagement. Neither circuit was effectively jammed but the fact that the enemy evidently has a set similar to the SCR-808 is considered worthy of note.

VISUAL:

No flag hoists or light transmissions were made by this ship during the engagement except at 0750 when three unidentified vessels appeared on the horizon to the south. In the absence of any intervening screening ship these ships were challenged by the GAMBIER BAY, using the 24” searchlight, with the effective three letter major war vessel challenge. All three vessels immediately sent the proper three letter reply, repeating several times. The following message was then sent to them: “BT WE ARE UNDER ATTACK BT K”. The center vessel “dashed” and “rogered” for the message. An attempt was further made to identify the vessels’ calls by sending AA but no reply was received. (Note: These ships may have been destroyers dispatched by commander Seventh Fleet from Leyte Gulf scheduled to relieve the three destroyers in the screen of Task Unit 77.A.3. It is thought by many survivors, however, that these proved to be enemy ships and opened fire on our ship.)

INTERCEPTS:

During the entire operation the following CW circuits were guarded: Bells, Manus Fox, Task Force Common, Fleet Common. From these circuits sufficient intercept traffic was received and broken to provide plots at enemy units moving in West Philippine waters.

REGISTERED PUBLICATIONS AND OPERATION ORDERS:

All publications and devices on open shelves or otherwise loose in the Code Room and Communication Office were placed in weighted canvas bags and jettisoned either in weighted bags or throw separate1y into the ocean. Those publications contained in the safes in the Code Room, Communication Office, Air Office and in the Confidential Locker adjacent to Air Plot were left and locked therein.

CIC and RADAR:

The equipment in CIC and radars installed were standard for vessels of this class. The performance of all equipment and personnel was highly satisfactory throughout the entire engagement. The SG Radar picked up the enemy force at 47,000 yards, about the same time as did similar sets in other CVE’s of the formation. Ranges were furnished Gunnery Control for fire control purposes as the enemy cruisers closed from the northeast within range of the 5″ gun. The radars and remote PPI’s were intentionally damaged just before abandoning ship. The IFF responder was removed and dropped into the water where it sank.

USE OF SMOKE:

As has been noted elsewhere in this report all ships of the Task Unit, on orders from the OTC, made and effective volume of smoke, which undoubtedly in combination with a rain squall, adversely affected the enemy’s gunnery and caused a reduction of damage to all CVE’s of the disposition, particularly from the heavy guns in the enemy’s main body. Smoke, however, afforded no protection to this ship from the fire of the cruisers on our eastern, windward flank.

OWN AND ENEMY TATICS:

1. Other than the employment of all possible speed there was little that the Task Unit could do to escape an enemy force with superior firepower and speed. The OTC used his screening vessels to intervene, make smoke, and attack the heavy ships with torpedoes and 5″ guns. At the same time he ordered all carriers to make smoke and set the course to the southwest, in the direction of possible assistance from our own forces in Leyte Gulf.

2. The enemy used fast elements of his force to encircle our force. His ships gained station on three sides of this disposition. This was an excellent maneuver to use to prevent our escape and close us it our force had been only slightly inferior in firepower and speed to his own force, but he wasted valuable time in which he might have used a division of his fast cruisers to plow directly through our vastly inferior force, sinking each escort carrier in turn, without serious risk to himself. Our planes and destroyer screen perhaps gave him the impression that our force (Partially obscured by smoke) was stronger than it actually was.

3. What actually prompted the enemy’s decision to retire is a matter of conjecture. From our viewpoint he had no good reason. This is discussed in the special action report of 29 October by C.T.U. 77.4.3 and no doubt amplified in his latest complete action report.

4. Due to the slow rate of fire (over a minute between salvos) and the small patterns (4 gun salvos about 25 yards in diameter) the ship was able, by maneuvering to avoid hits for a considerable period. The salvos were apparently being spotted on in increments of about one hundred yards. Course was changed about twenty degrees when it appeared that the next salvo would be “on”. Invariably the next salvo would land where we would have been had we failed to turn. The salvos would fall well clear for a few minutes and then creep closer again until a hit threatened. Another small turn by us and another series of “misses” would follow. This “snake dance” lasted about twenty-five minutes until the range closed to about 10,000 yards when the ship was first hit at about 0810.

ENGINEERING:

5. Until forced to secure, the engineering plant functioned satisfactorily. Maximum speed was attained by changing burner tips to size 36, increasing oil pressure to 400 lbs per square inch, opening wide, steam valves in all four force draft blowers and increasing engine speed to 178 r.p.m.

6. Blowers as installed do not furnish sufficient air for complete combustion of oil at maximum speed. Top speed might probably have been increased by two knots had there been an additional blower in each engine room.

7. Flooding of both engine rooms required the simultaneous use of all available pumps. The capacity of these pumps was not great enough to control the flooding of the machinery spaces. It is recommended that a main drain suction be installed on auxiliary circulating pumps thereby increasing the total output of pumps which could be used to control flooding.

MEDICAL:

8. When General Quarters sounded, all four battle dressing stations, sick bay, Chief’s Quarters, conditioning room, after mess hall, made preparations to receive and treat casualties. Two of the battle dressing stations (Chief’s Quarters and conditioning room) treated casualties; the other two were wiped out before patients could be brought to them. The station in the conditioning room treated a small number of casualties before it was destroyed. In both the active stations, treatment, because of limited time, consisted of administration of morphine, control of hemorrhage, and the bandaging of wounds. By far the greater number of casualties were treated by shipmates nearby or by themselves; all hands had been carefully instructed in the administration of morphine, hemorrhage, control and bandaging.

9. In the water, after abandoning ship, first aid use continued by medical department personnel and then men and officers in the various groups. For the first twenty-four hours none of the personnel were excessively uncomfortable although a number of the severely wounded died. Lack of food and water was not a problem for this period of time, even among the wounded. After approximately thirty hours, a large number of the injured and many of the uninjured became thirsty and kept asking for water. It was at this time that restraint of many men to prevent them from drinking salt water became a serious problem. A small number of men became delirious; as time passed the number of these men increased and it was with difficulty that they were kept with their groups and prevented from drowning themselves. Several of these men had to be restrained from injuring the wounded and other members of their groups.

10. There were only isolated cases of attacks by sharks, although the majority of the groups had sharks in their vicinity. The two known attacks were on men with white skivvies or no clothes on at all. Both victims died within a few hours.

11. The length of time spent in the water varied from forty to forty-eight hours. Although suffering from sun, immersion, exposure and exhaustion most of the survivors were in good condition; a great many, however, developed ulcers on the anterior surfaces of the legs which were slow in healing but caused no difficulty in walking.

12. The importance of extensive training of all personnel in the fundamentals of first aid cannot be too strongly emphasized. This vessel held first aid lectures daily. The fact that the great majority of casualties either administered first aid to themselves or were treated by shipmates speaks for itself; many of the injured owe their lives to the first aid training of their shipmates. Control of hemorrhage administration of morphine and bandaging must be taught to all men aboard ship. In this action, as in many others, the easy accessibility of morphine and its free use on the wounded is of great importance.

13. Personnel on life rafts found the medical kits satisfactory in every way except for the difficulty in keeping the contents dry once the containers were opened.

14. Since none of the men, except some of the wounded, required water for about twenty-four hours, it may be concluded that conservation of emergency rations on hand may be effected by not issuing any for the first twenty-four hours. Hunger was never a problem.

15. Since morphine and drinking water are the most necessary items in the water, the following is suggested as a means of having each man carry his own supply: a belt with one or two (if possible) light canteens on it, and having two pockets in the front, one of which to contain a pack of morphine syrettes and the other water tight can containing twenty-four malted milk tablets.

RECOMMENDATIONS AND CONCLUSION:

16. In both the fast and escort carrier task forces, the practice of conducting dawn and dusk short range air searches characteristic of our peace-time maneuvers has gradually gone into discard until such searches have become the exception rather than the rule. Shore based searches and intelligence from other sources have been relied upon to provide all vital strategic information; and further, radar is being depended upon to a high degree to prevent tactical surprise.

17. It is therefore recommended that:

(a) All carrier task units operation independently maintain a dawn and dusk search of 360° to a distance of at least fifty (50) miles.

(b) At least one ship with SH (or better) radar be assigned to each carrier task unit.

18. This task unit (even though unsupported) could have raised havoc with the enemy if it bad had but an hours warning of impending contact. The advantage to the side able to effect tactical SURPRISE has been impressively demonstrated once more.

19. From the fragments of information available, it would appear that the enemy was able to steam through San Bernardino strait and proceed toward Leyte unreported and undetected until first men, reported, and engaged by this Task Unit. That this could be possible seems incredible at first. However, after further thought in the matter it appears that the divided chains of command for the Naval Forces in and near the Philippines for this operation may have been conducive to producing just such a situation. To guard against the possible occurrence of such a situation in the future, it may prove desirable to have all naval unite (Including all air units operating over the water and all submarines) responsible to a single Naval Commander. He should be in the combat zone, actively directing and tracking the movements of all major surface units, and initiating and coordinating all search operations (including those by air and submarine,). Such a Naval Commander could best evaluate and disseminate vital strategic information if not compelled to maintain radio silence.

20. The following are observations of the survivors regarding lifesaving and abandon ship equipment during the 40 odd hour period in the water. Remedial suggestions are noted after each deficiency or malfunction of equipments:

(a) Not a single water breaker on any raft retained potable fresh water not- withstanding the fact that all breakers had been refilled with fresh water only two days previously. The spigots were not adequate, they were either knocked loose when the rafts were dropped to the water or accidently kicked loose by personnel in the raft. The fresh water was either lost or contaminated by the sea. Here reliable and more sturdy water containers should be provided without delay. As a suggestion, individual sealed metal cans (similar to those in aviation personnel’s emergency rations) placed in a larger metal can might prove adequate. This would permit consumption of entire cans thus leaving no part of a can or breaker having once been opened exposed to the possibility of sea eater being mixed with the fresh.

(b) There were many severely sounded who died in the water who might have survived had they not remained immersed in the salt water. There were a few rubber life rafts among the survivors and these were used to carry as many of those wounded as possible. Recommend at least four three man rafts per three hundred men aboard. These rafts to be released from special metal containers placed along the sides of the ship with the regular rafts.

(c) In practically all the rafts the canvas bands and lines holding the grating in the bottom and life lines around the perimeter gave way shortly after they were in the water. These bands and lines should be tested and replaced frequently enough to prevent failure. In most cases extra line was used to re-lash the bottom gratings. Extra lengths of line of various size could always be used.

(d) For additional assurance that every man has a small amount of water, food and medical supplies the pockets on the kapok life jacket might be altered to securely carry a first aid packet and individual emergency rations. Also a recess be provided to contain a canteen which is easily accessible to be removed the change the water at frequent intervals.

(e) In all floater nets there were cases of increased irritation and resulting salt water sores caused by rubbing of the cylindrical buoyant components directly against the individuals in the net. This was very annoying and added to the discomfort of all concerned. If the size and shape of the buoyant components were altered to resemble a football, the irritant effects of contact would be eliminated.

21. The following suggestions are offered to increase efficiency of the damage control method: on this type vessel:

(a) Install in damage control center a remote control panel for the sprinkling system. This panel should be identical and in addition to those two already mounted on the hangar deck.

(b) Install an MC system with provision for shifting to emergency battery power with outlets at all repair party stations and at damage control center. (This would be in addition to the 21MC)

22. The Executive Officer‘s relentless enforcement of the provision that all men carry life jackets and wear full length clothing at all times in a combat zone in responsible in no small measure for the high percentage of survivors. A few men who discarded items of clothing in the water suffered most severely from sunburn and immersion.

R.R. Ballinger

* * *