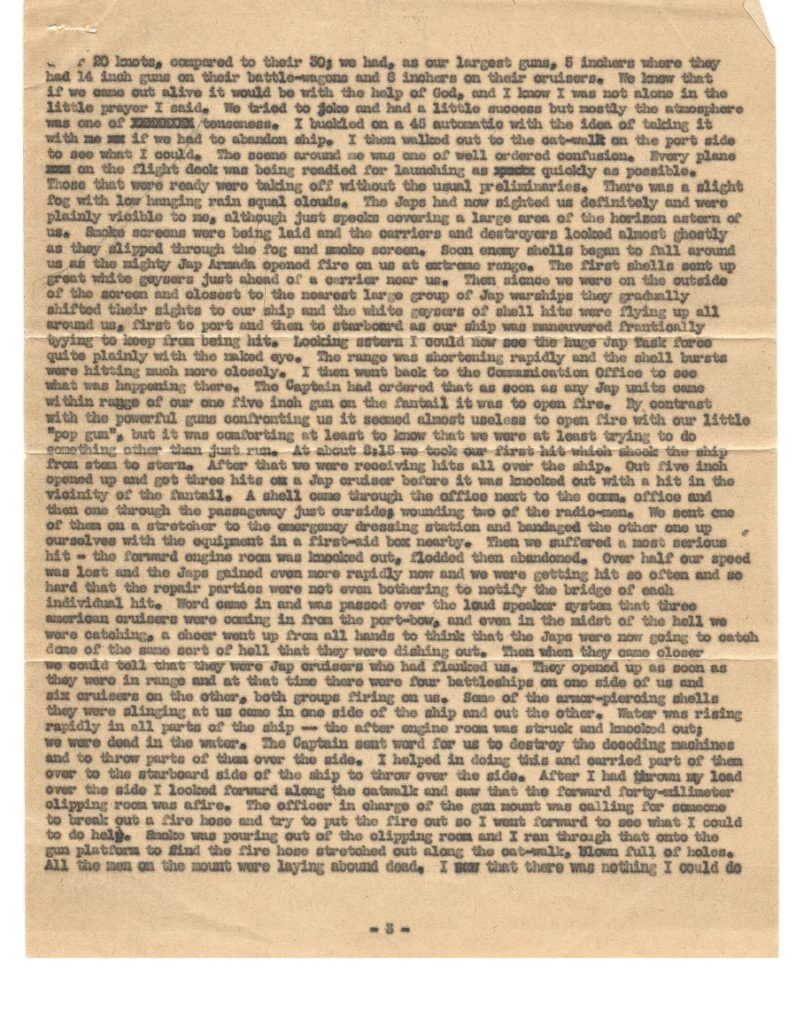

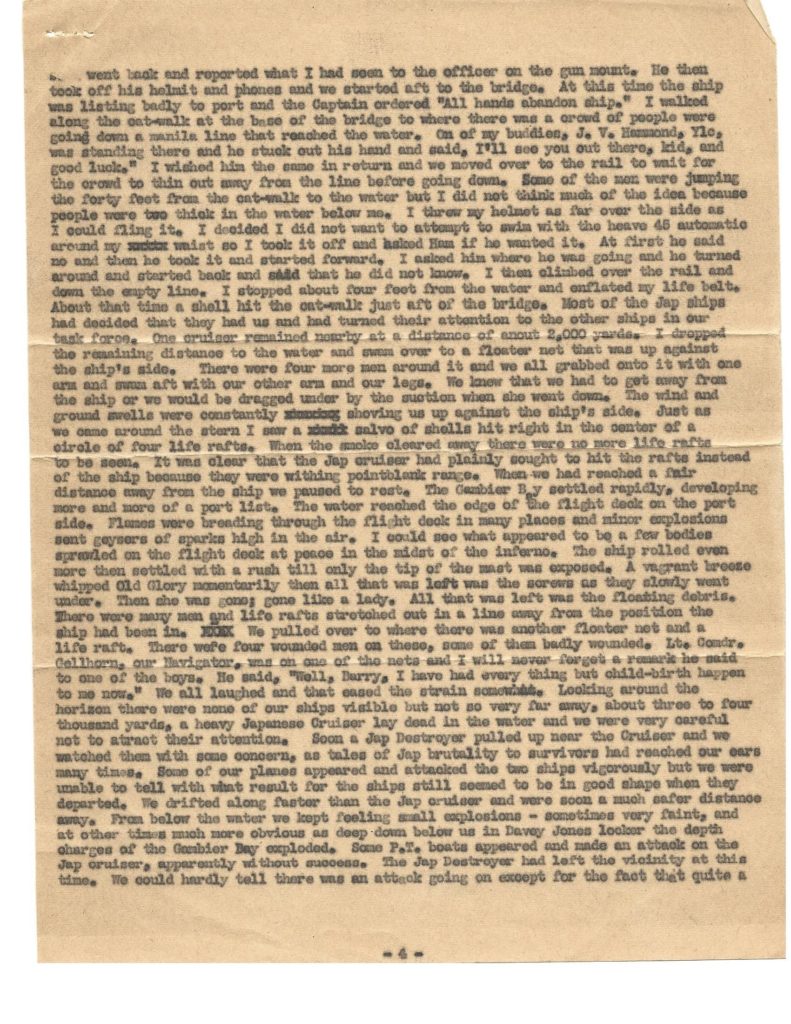

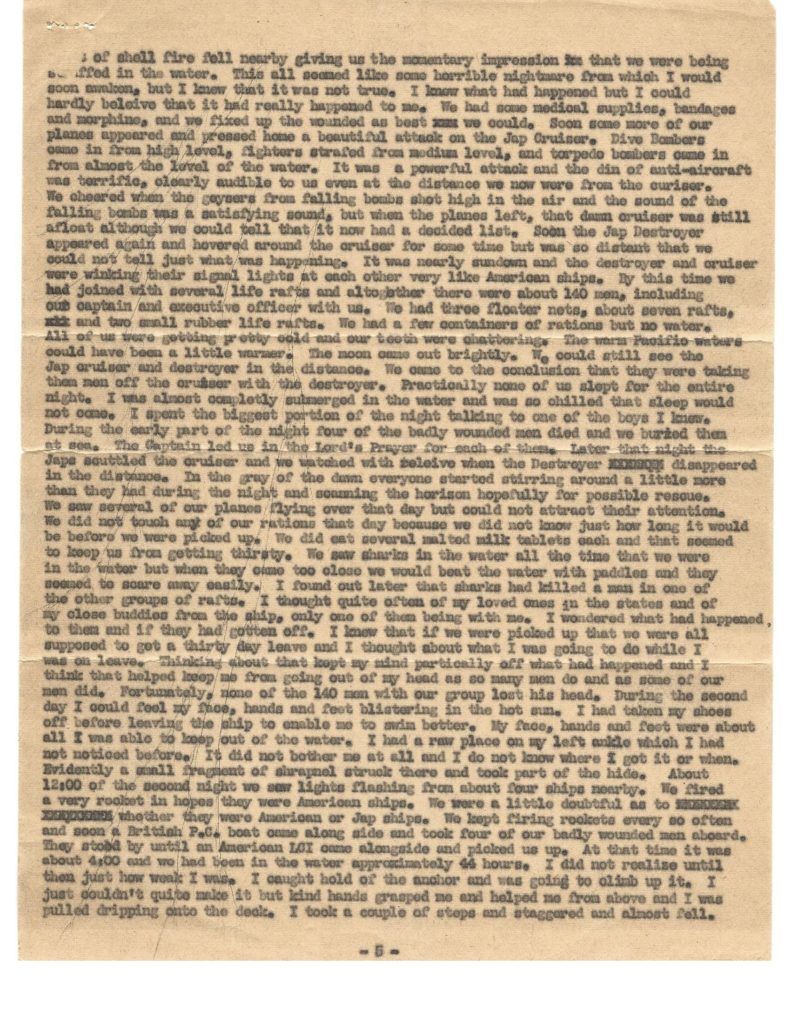

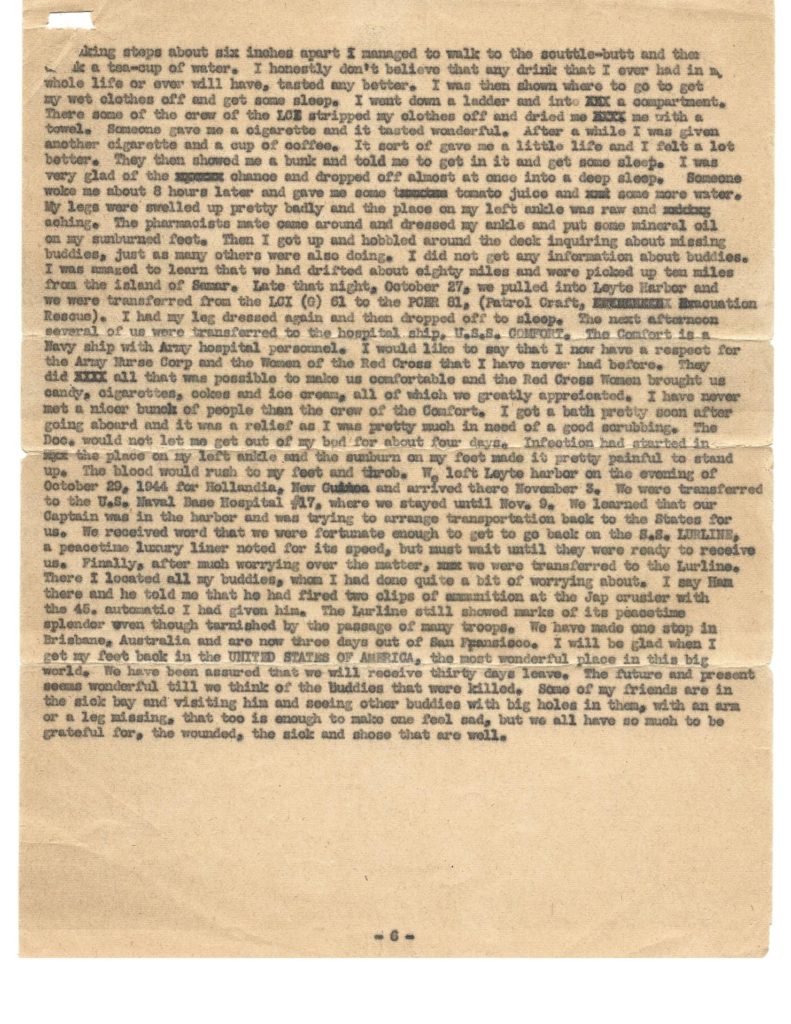

The Life and Death of the United States Ship Gambier Bay

By: Marshall L. Mitchell, Yomen

Marshall crossed the bar in May 1964

Submitted by Daniel Mitchell, son of Marshall

~ ~ ~ ~ ~

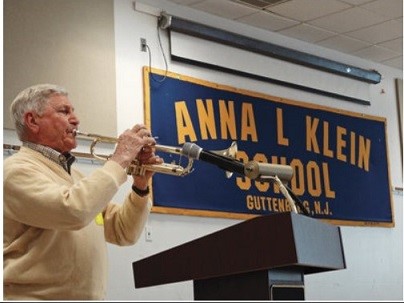

A Tribute to Our Vets

Anna L. Klein School Honors Finest for Memorial Day

Raymond Dipieto

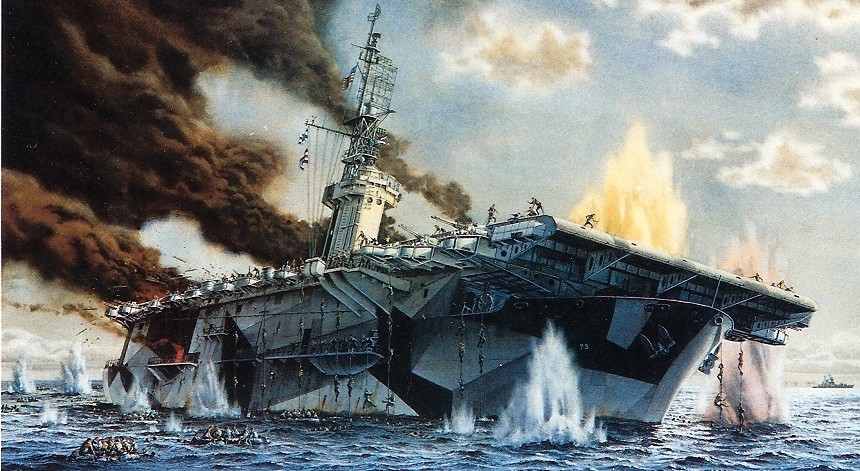

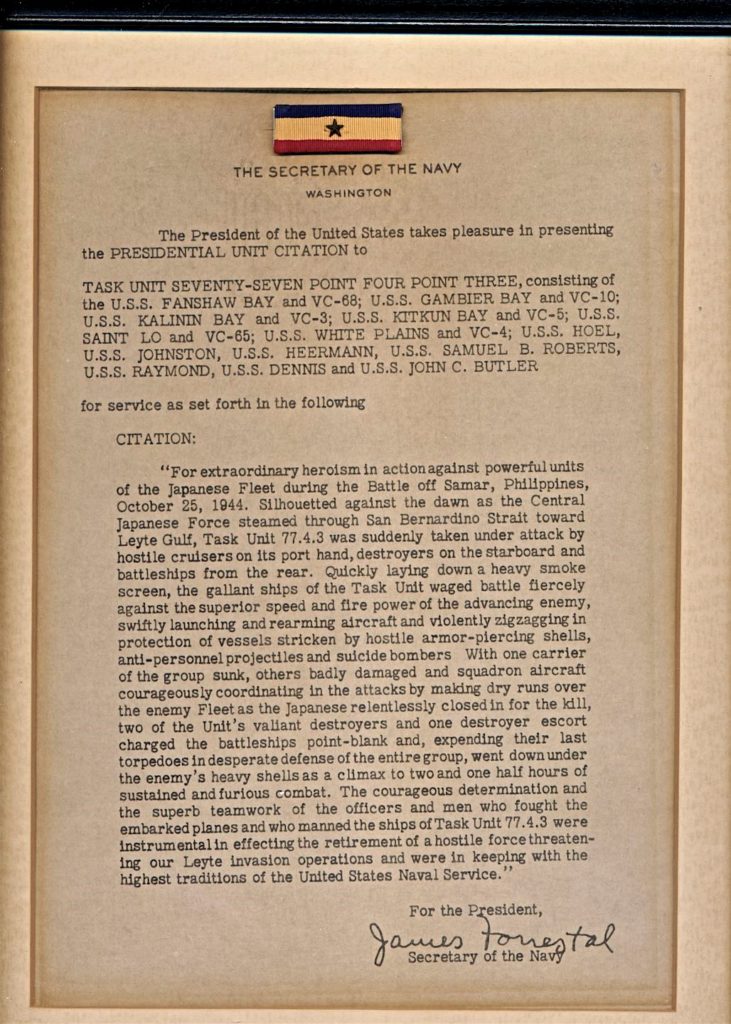

The memorials began at Anna L. Klein School with an event featuring a special spotlight on the Battle of Leyte Gulf. Fought in late October 1944, it was one of the largest naval battles of World War II and a decisive turning point in the Pacific war.

“When Macarthur was [returning to] the Philippines,” said Larry Giancola, chairman of the Guttenberg Memorial Day Committee, “the Japanese navy had a plan to lure Admiral Halsey’s battleship and aircraft carrier fleet away from the landing beaches so a superior force of Japanese battleships – including the largest battleship in the world, the battleship Yamato – could come in and raid the beaches. And the only thing that stood in the way of the main Japanese battle fleet was a little unit of destroyers, destroyer escorts, and baby aircraft carriers. And that unit was called Taffy 3.”

WWII veteran Raymond Dipietro, a sailor in Taffy 3, recalled his experiences in a vivid presentation to the students and residents of Guttenberg. His ship, the Gambier Bay, was fired upon by the Yamato, described by Dipietro as “the biggest, baddest ship ever built,” from a then-astonishing range of 17 miles away.

“And then the cruisers came in range, and we started to get hit,” he continued. “Our ship took 27 shells.”

The Gambier Bay was one of six American ships lost during the battle (along with 26 Japanese ships). Dipietro was one of the lucky survivors, although it wasn’t easy. First, he had to get off the sinking Gambier Bay and out of danger.

“You have to get away from the ship, because when the ship is going down, there’s a suction that will take you down with it,” he said. While he swam for his life, a Japanese cruiser passed close by but didn’t fire upon the men in the water – possibly because they thought the sharks in the water would get them.

Dipietro spent three hot days and three cold nights in a raft without food or water before being rescued.

As a former bugler in the Navy (and son of a WWI bugler in the army), Dipietro demonstrated his chops for the audience by playing reveille, mess call, taps, and other military calls.

The afternoon presentation also included the school chorus singing “Anchors Aweigh,” several Memorial Day readings by students, and the presentation of awards to winners of an essay contest focused on the Battle of Leyte Gulf.

Later that day the memorials resumed as the annual parade kicked off at 68th St. and Madison, winding through town and ending up at Monument Park on Boulevard East.

Despite a light rain, a substantial crowd gathered to hear Rhonda Reid sing and Mayor Gerald Drasheff speak of the significance of the day, thanking those who served their country in defense of freedom.

The article was written in June 2014 by Art Schwartz, Staff Writer for the Hudson Report

~ ~ ~ ~ ~

The Battle of Leyte Gulf

By Ariana Kanze

Ariana Kanze is just 12 years old and a daughter of friends of Jennifer Wheeler (daughter of Owen “Wheels” Wheeler). Ariana was very interested in meeting our survivors and she stopped by to talk to them at our 2017 reunion in Seattle, where she resides. She has written a wonderful story about the men she met that day. Please click on the link below Ariana and Charlie’s photo to access the full story.

The Battle of Leyte Gulf by Ariana Kanze

~ ~ ~ ~ ~

My Memories of CPO Louis Nucci (Lt.)

By Al Whitney

I was born and bred in Brooklyn, NY a short ride from Floyd Bennett Field which later became NAS New York (Brooklyn). I remember my father taking me and my cousin there when I was very young. It was a gathering place for some of the world’s famous pilots in the 1930’s.Opening day had a flyover of 500 aircraft. Military and private planes. Doolittle, Lindberg, Earhart. “Wrong Way Corrigan” all were there at some time when it was open. When we returned home my mother asked if my father had flown with us. The answer was NO. My mother was not happy! I think it cost $5.

You can read about the history of Floyd Bennett Field in Wikipedia. Very interesting. Includes account of NAS NY(nobody calls it Bennett Field except Wikipedia).

My father was an Equipment Engineer with the NY Telephone Company and had to go NAS Brooklyn to see what they were requesting. And, of course my father meet with CPO Nucci. They were about the same age and he had a son my age. We were both in High School.

It was the start of a close family friendship. My mother and his wife Bea were good friends and they also lived in Brooklyn not far from the field.

On my first visit to the field with his son we were picked up at the gate by two sailors in a jeep and taken to the hanger where Lou had his office. What a thrill. It was huge and high, and we went to the top where you could observe all the aircraft in the hanger that was being repaired. Next we went into the control tower and watched the landings and watching the planes with wings folded going to their hangers.

I remember trips to the field and to the beach at Fort Tilden with the Nucci ’s. He also made a Ping Pong table for our basement that could be reversed to use for trains along with converting a 25 lb. sand bomb into a umbrella stand or ash tray. Nothing wasted. Wish I had it today.

CPO Nucci was promoted to LT. USNR in 1949. I was at the field and he asked me if I would go on his first visit to the Officer’s club. I was thrilled. When we went into the Club all the officers that were there started to yell at him. “You’re in the wrong club”. You don’t belong in here, you belong in the CPO club”. All with big grins of their faces! I know they all loved him!

I also remember his story of the Gambier Bay and his rescue. He could not smell so he always carried his gas mask. During the attack someone who panicked grabbed him from behind in a choke hold. He was lucky that someone was able to come along and save him.

When he was on the raft he said one minute you were up to your neck in water and the next minute out of the water. The rafts were very crowded. A steward swam up to the raft and people were yelling “there’s no room for him Chief.’ He told the steward to hold on next to him.

When he was rescued by an LST he was lifted up the side in a wire basket he had lost the last two fingers from his right hand. There was an air raid and he stayed half way up the ship until it was over. He thought it was the end. He came home with .25 cents and his uniform.

Anyone who was there or read about it knows how bad it was.

Nucci crossed the bar in 1983, his wife Beatrice passed in 2007.

~ ~ ~ ~ ~

2017 USS GAMBIER BAY ASSOCIATION REUNION

Eulogy in memory of Lt. Robert G. Young

By: Philip Young, Son of Lt. Robert G. Young and Ruth Baum Young

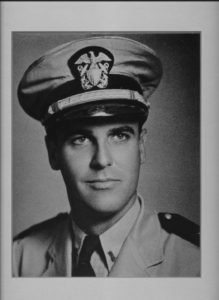

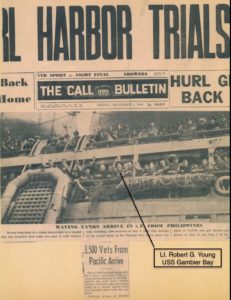

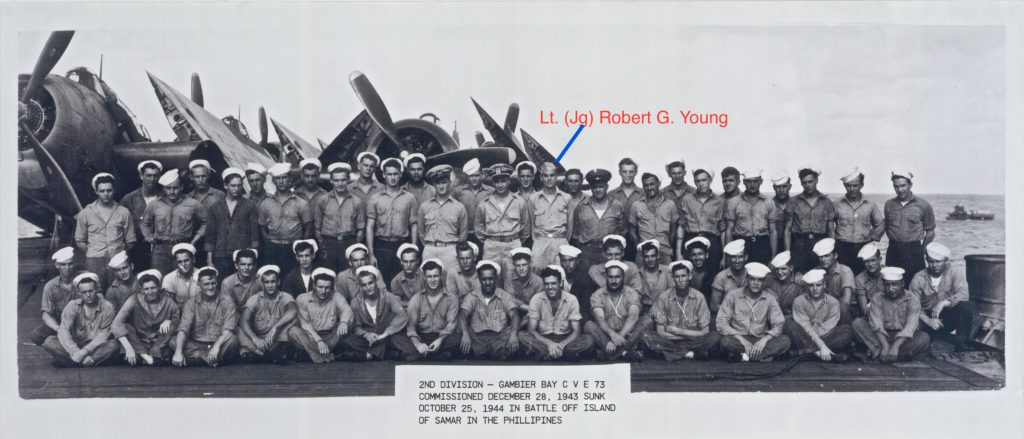

I am deeply honored to be invited to deliver a eulogy at this event in memory of my father, Lt. Robert G. Young, who served as a gunnery officer in charge of the 2nd Division on the USS Gambier Bay, which was sunk by the Japanese Armada in World War II during the Battle of Leyte Gulf, which historians described a as the “greatest naval engagement ever fought.”

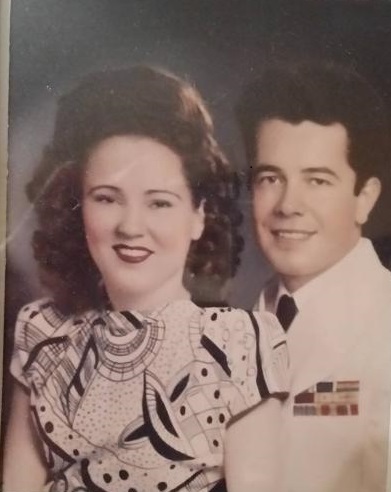

- Lt. Robert G. Young

- Robert and Ruth Young

Seven years ago, I discovered the USS Gambier Bay Association website and was rewarded by the opportunity to learn about the experiences of other survivors who had shared some of their stories. I was enthralled by the personal accounts of survivors Norm Loats and Charles Heinl. When I contacted Paula Grond, the President, and Marlene Hughes, the Treasurer, I received a warm welcome to join the association and to meet survivors and family members at the October memorial gathering being held in St. Louis.

When talking with Bud & Darlene Petit during the banquet dinner, I was to learn that Bud knew my dad and considered him “a real good officer” on board the Gambier Bay. Bud revealed that he was only 17 when he enlisted and was assigned to one of the 20MM guns on the carrier.

After the memorial service, one of the family members excitedly told me that I should meet with Murray Brown who knew my dad on the ship. Interviewing Murray turned into one of the unexpected highlights of the trip for me as he confirmed that he and my father were in the same unit together and remembered him as an officer whom he liked and respected. He was proud to share with me a photo picturing Lt. (j.g.) Young standing in the third row of his 2nd Division directly behind Murray seated in the front row on the flight deck.

In later reunions, I got better acquainted with Norm St. Germain, Dean Moel and Carl Amundson who shared heartwarming stories with me about their interaction with my dad. Carl fondly recollected the time when Lt. (j.g.) Young said he was going to promote him to the next level “Seaman” as long as he passed the exam. When Carl replied “I ain’t taking no dam written test”, my father smiled knowingly, waived the exam requirement and promoted him anyway.

Dean Moel confided in me that he was shocked to be wrongfully fired from his kitchen duties and transferred to the flight deck for the Air Division. He was so upset that he marched over to the officers’ quarters, explained to Lt. (j.g.) Young what had transpired and asked to join his 2nd division. Dean was relieved when Young immediately arranged for him to be reassigned to his unit.

I was surprised by the good condition of the survivors at this stage in their lives. The mystery of their relatively youthful appearance was cleared up when I learned that many of them had enlisted at the tender age of 17 when they needed their parents permission.

Born in 1912, my father was more than a decade older than many of the young sailors when he became an officer on board.

Growing up in NJ & CT, my dad was a high achiever who became an Eagle Scout and the valedictorian of his high school class. After graduating from Dartmouth College, he began his career at the Travelers Insurance Co. and later became President of an insurance agency in Pittsfield, MA. In 1941, he married Ruth Baum, daughter of a noted Pennsylvania impressionist artist, Walter Emerson Baum. Mom and Dad were loving parents who were always loyal to each other during their 49 years of marriage.

During the post war 50’s, my older brother, Rob, and I grew up in Pittsfield, MA as my father built his insurance business and my mother worked as a teacher and a librarian. We played baseball, football, tennis, skied and had snowball & apple fights with our neighborhood gang of “little rascals”. When we watched “Father Knows Best” starring Robert Young on TV, we assumed our father, with his movie star looks, was the real one because he had the same name and, as far as we were concerned, he did know best.

When we got to see “Mister Roberts”, the 1955 war movie about a ship in the Pacific, starring Henry Fonda as an officer confronting the volatile captain played by James Cagney, we imagined our dad had similar experiences in the Navy. Mom told us that Dad was popular with his men and stood up for his sailors when he felt the first captain on the Gambier Bay was being unreasonably tough on them.

Then when our family visited a fellow Navy man’s home to watch Victory at Sea episodes, we got to see reenactments of thrilling naval battles with the Japanese in the Pacific Theater. Too young to grasp the full impact on my dad and other survivors of their aircraft carrier sinking in the Battle off Samar, I did not fully understand that, if he had not survived, I wouldn’t be alive as I was born in 1947 well after his return from the war.

We feel fortunate that our oldest son, Wendell, interviewed my mother for his 8th grade history project about WWII so we have a tape of her account of Dad’s war experiences. When Pearl Harbor was attacked, Dad first tried to enlist in the Air Force but was told that he was a few days too old to fly at the age of 29, instead he signed up with the Navy for an officer training program at Princeton Naval Training School to become a gunnery officer. Then he was sent to Montara, California to train 40 men on the ocean shooting range prior to being assigned to the Gambier Bay.

My mother recounts that his training proved effective during the battle near Saipan. When he spotted a plane attempting an attack on the carrier, he swiveled one of his gunners around just in time to shoot down the diving aircraft. Mom told us the episode was captured in a photo that was printed in Time magazine on July 24, 1944.

In a letter home dated October 2, 1944, Dad wrote “I am on a carrier, which is all I can say in general. I am 2nd division officer in charge of the deck and gunnery division, with 70 men to look after with the assistance of two junior officers. Recently, I qualified as “Officer of the Deck” in full charge of the ship subject only to the Captain. These duties include “directing the helmsman, checking the signals, decoding transmissions, knowing the latest technical data, and in general being in charge of the organization and maneuvering of the ship. Aircraft activities and the movement of other ships add to the excitement. It is the toughest watch aboard, and one where you catch the most hell, but offsetting that is the satisfaction in running the show for a few hours each day and night.”

On October 25th, Lt. (j.g.) Young had just completed his duty as “Officer of the Deck” on the aircraft carrier and had gone below to get some breakfast just before Admiral Kurita’s force of battleships, cruisers and destroyers was spotted. In his written notes about the events, my father recalled that “Lt. Richard Elliott announced that ‘A strong task force is 25 miles astern of us & closing.’ General quarters clanged & the ship was instantly veined with snakelike files of men running to battle stations. I made my way to the bridge and joined the rush for steel helmets, talker phones & binoculars. I was to man a telephone that controlled the 40MM batteries. Suddenly geysers of water were splashing up inside our formation in salvos of 2 to 4 shells. The battleships & cruisers had opened fire from about 18 miles. We were under attack. Chaplain Carlson stood near me giving a play by play description of the action to the men below decks over the PA system. At 0715 we took the first hits. The ship gave a shudder as a salvo of heavy shells landed in the middle of the after elevator at flight deck level. Suddenly the Gambier Bay gave a violent shudder, as though she had been mortally struck. ‘The forward engine room is hit & water is rising,’ announced the bridge squawk box. At 0840 we were dead in the water. At 0842 Lt. Warren Stringer, gunnery officer, swung from the captain & screamed ‘Abandon, ship, abandon ship. ’Into my head phones I repeated, ‘Abandon ship, abandon ship.’ Then there were hundreds of us in the water. I concentrated on staying afloat and trying, unsuccessfully, to inflate my life preserver. I reached the nearest raft with my last stroke. Seaman Elledge held my head out of water until the nausea had passed. Ensign Epping called me aside and pointed below us. Down 15 feet were several monster sharks, shadowing us. No one became panicky at sight of them. A few violent kicks kept them at a safe distance. Had we known that one of our shipmates who was swimming in his skivvies had been attacked and killed by a shark, we would not have been so nonchalant. The Gambier Bay was listing badly to port now. Some ammunition, probably 40mm, was popping & flashing. As she disappeared, a cheer rose from the next group of rafts – a tribute to the only carrier ever sunk by surface shell fire.”

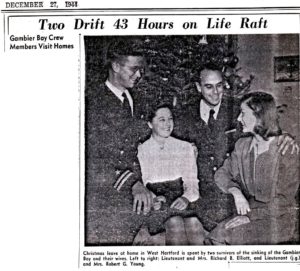

For approximately 43 hours, my dad and the men in his flotilla clustered around the raft which he described as “a partly submerged piece of doughnut-shaped wood in unstable condition”. Then before dawn on October 27th, an L.C.I. troopship spotted them with searchlights and picked up the survivors. Weeks later they arrived back in San Francisco where Dad called Mom on December 2, 1944, which happened to be her birthday, to share the wonderful news of their rescue! On December 27th, long-time friends and shipmates on board the Gambier Bay, Lt. Richard Elliott and Lt. (jg) Robert Young and their wives were joyously reunited in Hartford for a newspaper interview about their Battle of Leyte Gulf experiences.

The commitment of the survivors and family members to carry on the remembrance of the heroic Gambier Bay sailors is extraordinary. I know many of you have been attending annual reunions for a number of years. My dad has always been my hero, a warm caring father, who was proud of the selfless acts of courage of his fellow sailors whom he considered the real heroes of the Battle off Samar.

In his later years, Dad courageously fought a personal battle with the debilitating effects of Parkinson’s disease. As Mom and Dad struggled to maintain their quality of life together, his optimistic personality and warm sense of humor kept us hopeful and connected with him. I wish that Mom and Dad had learned about these annual association gatherings and been able to attend reunions prior to my father’s passing away in 1991. He would have relished the opportunity to reunite with his shipmates.

I am grateful to have formed friendships with a number of survivors and to have gleaned glimpses of his character from the inspiring stories they have graciously shared with me. My sincere thanks to all of the survivors and family members who were inspired to create his extraordinary association to keep alive the memory of the heroic sailors of the Gambier Bay and its sister ships for future generations.

Robert crossed the bar in 1991

~ ~ ~ ~ ~

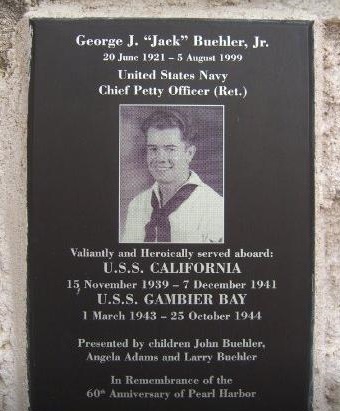

Memorial Plaque for George J. “Jack” Buehler, Jr.

National Museum of the Pacific War – Nimintz Museum – Fredericksburg, Texas

* * *

George and Ann Buehler, Jr.

Wedding Photo – May 24, 1946

Dad met Mom sometime after the war. Her name was Ann Leona Ballard and was from the Waco, Texas area. My Mom and Dad were married on May 24, 1946 and honeymooned in Houston, Texas at the Rice Hotel. On January 12, 1950, they had their first child, a boy, who was named George John Buehler III. On September 1, 1951, my sister Angela Ruth Buehler was born. I was born on September 30, 1952 and am the youngest child in the family. We three children are still alive and doing well. We lived in Hawaii for 2 years from 1957-1959 and moved back to the mainland when Dad retired from the Navy after 20 years of service. We moved to the Clear Lake City area near Houston where Mom and Dad both were employed in the Aerospace industry (Dad with TRW and Mom with Boeing). There, they raised us kids and enjoyed life and eventually had 5 grandchildren added to the family. As you know, Dad passed on August 5, 1999 of a heart attack. He was given a beautiful seaside service with military honors by the US Navy in Corpus Christi, Texas. Mom continued to live near Houston until her passing on November 12, 2007. They are both greatly missed!

George crossed the bar in August 1999

Ann passed in November 2007

*

Story and photos submitted by his son, Larry Buehler

~ ~ ~ ~ ~

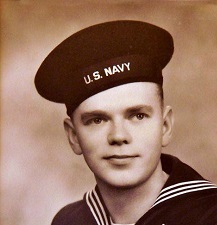

Moss Junior Kelly

Moss Junior Kelly grew up on his family’s farm in Smithport, Pennsylvania. He graduated from high school at age 17 and immediately joined the Navy, without telling his family, to serve in World War II. He was 22 years old when he was assigned to USS Gambier Bay where he worked as AMM 2/C. His station was on the flight deck where he repaired plane engines.

He laughed every time the told the story of crossing the Equator and the crazy wigs and outfits everyone wore. He also laughed when he talked about the time a plane missed one of the landing wires and ran into the barrier.

Moss spoke of the sinking of the Gambier Bay and spending 72 hours in the water with tears in his eyes. His group of “about a dozen men” was separated from the other survivors and they had no food or fresh water. The wounded men were in the middle of the life raft and he held onto the rope that ran around the perimeter.

Moss prayed for the group often, if not constantly, during the 72 hours. One of the men clung to his arm, thinking he could get into Heaven with him if they were not rescued and died at sea. The group was finally picked up by a PT. Moss spent time in the hospital having skin grafted from his leg to repair the hole that was eaten in his arm from the clinging. He was awarded the Purple Heart.

He had a large scar on his arm and an immense scar in his memory from the hell he endured. At the time the Gambier Bay was sunk, his father woke up in Pennsylvania and sat bolt upright in bed in a cold sweat. His brother, Kenneth Kelly, watched the Gambier Bay’s gunfire from his own battleship, the USS California at Suriago Bay.

He was responsible for several patents on plane repair, served in the Korean and Vietnam wars, and was trained as a technical writer. He retired as a Chief Petty Officer after serving 22 years in the U.S. Navy. After retiring he worked as a technical writer for NASA and GE.

He loved gardening and passed that love on to his children and grandchildren. He enjoyed bird watching and fishing. There was nothing he couldn’t make from wood and nothing he couldn’t fix. He helped anyone in need and always had a smile on his face. He loved our country and the Lord.

He was a fantastic father. Moss “crossed the bar” after a stroke on January 23, 2006.

Story and photos submitted by his daughter, Kathy Day

~ ~ ~ ~ ~

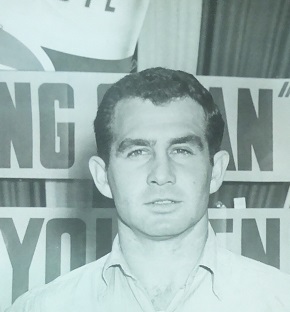

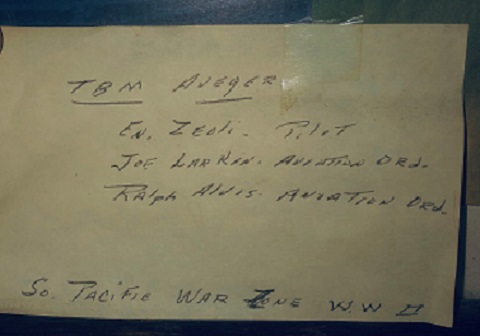

Ralph N. Alvis Memory As Told By His Grandson, Michael Alvis

My Grandpa, Ralph N. Alvis was among the many crewman of the USS Gambier Bay. The stories he told me, I can’t even begin to fathom. I hope to be half the man my grandfather was.

The picture above, with the Freedom’s Cost lithograph in the background, is of him at a birthday party in circa 2007. I only have two pictures of Him, the one above and one when he was younger.

Below is the note that my grandfather had on the lithograph.

I want to let our veterans and his crew mates know that they are not forgotten and they are loved.

To all of the crew mates, those that have crossed the bar and those that are still alive, know that you are not forgotten and you are loved.

Your service means so much to me, thank you!

Ralph crossed the bar in December 2008

~ ~ ~ ~ ~

Crossing the Equator Photos

Submitted by Breanna Ricciardi, Granddaughter of Vincent Ricciardi

Vincent crossed the bar in April 2016

~ ~ ~ ~ ~

Henry and Virginia Rosinsky

January 13, 1945

Our Lady of the Miraculous Medal Roman Catholic Church

Ridgewood, Queens, New York

Henry crossed the bar in April 1993

Virginia passed in 1978

* * *

Life Long Friends

Vincent Ricciardi (L) was the Best Man at Henry’s Wedding

~ ~ ~ ~ ~

Surviving Taffy 3

Growing up on the family farm in Breckinridge, in the middle of landlocked Oklahoma, young Rex Campbell had the ocean on his mind.

“I’ve always wanted to be in the Navy,” he said.

After the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor, drawing the United States into World War II, Campbell decided to join the Navy rather than take his chances in the draft.

“I never did think I’d like to dig a foxhole,” he said, smiling. “When we got out there in the water, I kind of wished I was where I could dig one.”

He especially wished that when his ship was sunk by Japanese surface fire during the Battle of Leyte Gulf. But his story begins long before that fateful day.

In November 1942, at 20 years old, Campbell, the third of six children, joined the Navy.

He was sent to Naval Station Great Lakes for training. Since he had attended welding school and briefly worked in the aircraft industry, the Navy assigned him to aviation metalsmith’s school.

After 26 weeks of school, Aviation Metalsmith 2nd Class Campbell was assigned to the U.S.S. Gambier Bay.

The Gambier Bay was a Casablanca-class escort carrier, also known as a jeep carrier or a baby flattop, because they were smaller, less armored and cheaper to build than their larger fleet carrier counterparts. The Gambier Bay was dubbed CVE 73 (the crews of the baby flattops joked that CVE stood for Combustible, Vulnerable and Expendable). It was the 19th and last such carrier built in 1943 by the Kaiser Shipbuilding Company in Vancouver, Washington.

Campbell boarded the Gambier Bay not long after it was commissioned in late 1943.

May 1, 1944, the ship sailed with a crew of 860 and a complement of 30 aircraft to join the 7th Fleet as part of the invasion of the Marianas.

When the Gambier Bay was launching and recovering aircraft, Campbell worked with the landing signal officer, letting him know whether the planes had their flaps, landing gear and arresting hooks down. He also worked in the aviation sheet metal shop, welding and repairing the metal skin of the ship’s airplanes.

The Gambier Bay saw a lot of action, supporting the landing of Marines on Saipan, then supported U.S. action on Tinian, Guam, Peleliu, and Angaur.

September 19, 1944, the ship joined an escort carrier task unit in Leyte Gulf. The task unit, dubbed Taffy 3, consisted of six escort carriers, three destroyers and four destroyer escorts, and was stationed off Samar.

When Admiral William “Bull” Halsey’s 3rd Fleet left Leyte Gulf to engage the Japanese in the Sibuyan Sea, the ships of Taffy 3 were the only ones still in the area off Samar. But the Japanese fleet turned its attention to Leyte Gulf. On October 25, 1944, four battleships, six heavy cruisers, two light cruisers and 11 destroyers steamed off the coast of Samar, bound for Leyte Gulf.

Taffy 3 was all that stood between the approaching Japanese ships and Leyte Gulf, so the task force turned to fight. U.S. planes launched from the escort carriers attacked the Japanese ships until their ammunition ran out, then flew dummy runs to slow the enemy’s advance.

The escort carriers put out smoke screens to try and cover their escape while U.S. destroyers engaged the enemy. But the carriers came under fire nonetheless and the Gambier Bay, at the rear of the formation, was pounded by Japanese surface ships.

The Japanese were using shells containing different colored dyes. When a shell hit, spotters would relay the information to the gunners, who would then adjust their aim. One such shell struck near Campbell, splashing him with red-dyed water.

“That water splashed up and got on this arm and I looked down there and saw the red and I thought it was blood,” he said. “But I didn’t have a scratch on me.”

Around 8:20 a.m. on October 25, 1944, an 8-inch shell struck the Gambier Bay and flooded the forward engine room, cutting her speed in half. Before long the ship was dead in the water and was listing badly.

Campbell was battling fires near the ship’s stern when he heard the call to abandon ship.

“I looked out there and there were just guys everywhere in the water,” he said. “There just wasn’t anyplace to jump. I was darn glad I didn’t because I had my helmet on. I might have stretched my neck out.”

Campbell slid down a line hanging off the side of the listing ship and dropped into the oily water. He began to swim for all he was worth.

“I thought I could swim away from the ship,” he said. “I was really going, I thought I had gone a long way. I looked back and there that darn ship was. I guess I was going against the tide.”

He turned and swam along the side of and away from the doomed ship. The aircraft carrier didn’t stay afloat very long. At 9:07 a.m. the U.S.S. Gambier Bay capsized and sank.

“It went under so fast when it got ready,” said Campbell. “It just rolled over and kind of come up and, boy, it was gone. I didn’t think they would go down that fast.”

Campbell swam to a floater net designed to keep sailors afloat, if not out of the water. There was a life raft as well, but it was filled with wounded men.

“We put our heads in the middle and we could rest our head on one another’s shoulder and put our feet to the outside,” Campbell said.

There were roughly 16 or 18 men on the floater net and in the raft, Campbell said.

Not long after they went into the water the men had unwelcome company — a Japanese ship. The Japanese sailors stood at the rail, watching their helpless enemy.

“They were so close you could see their teeth,” Campbell said. “We thought they were going to shoot at us. But they didn’t.”

The Americans quickly drifted away from the Japanese ship, which Campbell surmised had been damaged by U.S. fire.

Campbell’s group then had inhuman visitors – sharks. They circled ominously underneath the raft and floater net until someone suggested noise might scare the deadly fish away. So, the men took knives and pounded on the floater net’s steel frame. It worked. The sharks left, never to return. Other groups of survivors weren’t so lucky, as several offered accounts of shipmates lost to sharks.

The men had no fresh water and no food, other than a few crackers. The nights weren’t bad, Campbell said, but the days were blistering. He had a cap to cover his head (“I didn’t have much hair then, either,” he joked.), but he had kicked off his shoes before swimming away from the ship and his feet quickly became badly sunburned.

As the hours wore on, some of the men became delusional.

“The first day it wasn’t very bad,” Campbell said. “But the next day there were some guys getting kind of delirious. They were seeing water fountains and women. I couldn’t see any of that stuff and actually, I thought there might be something wrong with me.”

A couple of the men tried to reach those phantom water fountains and were lost.

“That second day was bad in the daytime because it was so hot,” he said.

In all, two escort carriers, two destroyers and a destroyer escort were sunk in what is known as the Battle of Samar. But in all the time Campbell and the men he was with were in the water, they never saw another soul.

Campbell and his shipmates were in the water just short of two days, some 46 hours, before they were rescued by an American PT boat. They had drifted some 30 miles from where the Gambier Bay went down.

The PT boat’s crew offered the exhausted survivor’s coffee and cigarettes. Campbell neither smoked nor drank coffee, but this once he made an exception.

“I drank coffee, we were thirsty,” he said.

The rescued men then were taken to a hospital ship in Leyte Gulf. When they were strong enough they were transferred to the S.S. Lurline, a civilian ocean liner pressed into military service during the war, which took them first to Australia, then to San Francisco.

“There was a swimming pool on there,” Campbell said. “Of course, we didn’t need the swimming pool.”

As the ship sailed into San Francisco Bay, the captain told the men to stay on their side of the ship, not to crowd the rails on the side toward the Golden Gate Bridge for fear the vessel might capsize. They didn’t listen, of course.

“I was scared to death,” Campbell said. “I thought ‘man, this thing is going to turn over,’ but it didn’t.”

After being examined by doctors, Campbell was returned to duty. He spent the rest of the war in Pensacola, Florida., and was discharged in 1946.

The crew of the Gambier Bay shared in a Presidential Unit Citation and four battle stars. The Gambier Bay had the distinction of being the only U.S. carrier sunk by enemy surface fire during World War II. Miraculously, nearly 800 of the Gambier Bay’s crew survived, while more than 130 were lost.

After leaving the Navy, Campbell came home to northwest Oklahoma, where he did various jobs before returning to farming. He farmed around Pond Creek and Hunter until 1995, when he retired. Along the way he married and raised two children, then raised a grandson after his daughter died of a heart attack.

Today Campbell resides at Burgundy Place, where he enjoys rooting for the St. Louis Cardinals and Oklahoma State Cowboys.

* * * * *

Published By Jeff Mullin, Senior Writer, Enid News and Eagle (Oklahoma) – July 31, 2014

Submitted by his niece, Patty Ann Campbell

~ ~ ~ ~ ~

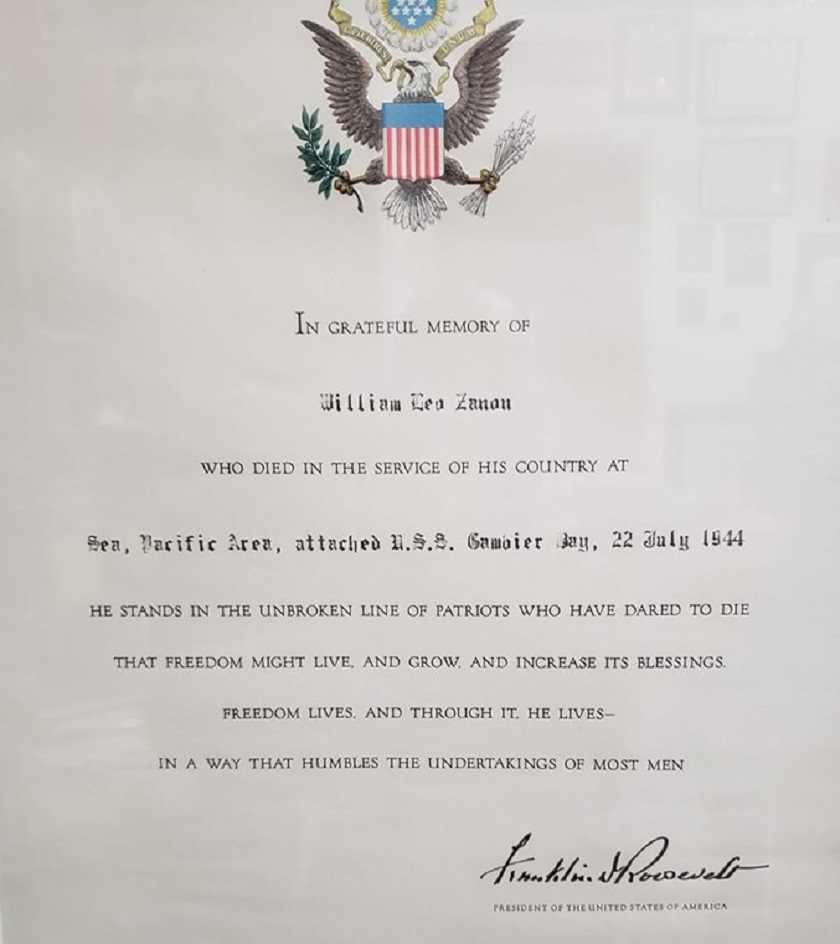

In Grateful Memory of William Zanon

Submitted by His Great Nephew, Bill Fletcher

William was KIA on July 22, 1944, at the Battle of Saipan when the plane he was on crashed into the ocean after take off.

~ ~ ~ ~ ~

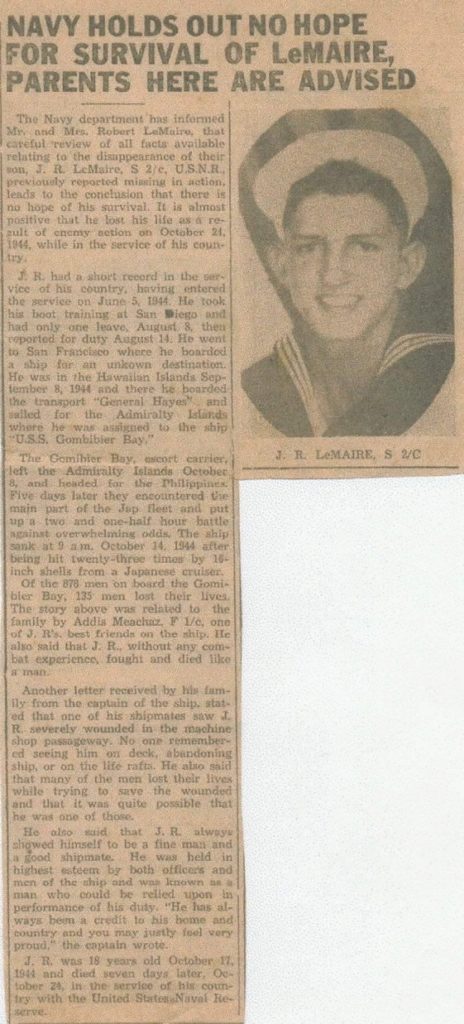

Obituary of John Robert (JR) LeMaire

Newspaper article submitted by George LeMaire, nephew of John

John was Kia

* * *

Vincent Anthony Ricciardi – Receiving the Bronze Star