Carrier Life Poem

By Lt. John P. Sanderson

“Carrier life is something” we’ve all heard people say, “If you’ve missed this grand experience, get your transfer in today.” But when it comes to flying, you can put me on the shore. For life on a CVE is something worse than war!

They get you up at three o’clock with a whistle and a bell. And you stand by in the ready-room just sleepier ‘n’ hell. Word is passed to man the planes, and you race out on the double. Then word is passed to go below, there is no end to trouble.

You’ll be sitting in the cockpit when Borries says “fly off!” You jam the throttle forward, and the engine starts to cough. You go rolling down the deck, but you always feel the need. Of just one extra knot to keep above stalling speed.

Or you’re up on ASP, or combat air patrol. Your gas is almost gone, and your belly’s just a hole. You’d like to eat, you and your plane have both been cruising lean. But airplot says to orbit, there’s a bogey on the screen.

Sometimes we’re told to scramble, and you go charging to your plane. But you sit there twenty minutes while the shrapnel falls like rain. When the enemy is gone, the Admiral says “Let’s go!” So you retire with your gear to the ready room below.

They put you on the catapult, and secure you in the gear. Pilgrim sticks his finger up, and looks up with a leer. You’re drawing forty inches when Charlie points “away”! And you hope to hell you’ve power to get in the air and stay.

It’s when you’re landing back aboard that you find it really rough. You’re high, you’re fast, you’re low – Christ Mac!! that’s slow enough! You’re out, you’re in your gear, and now Krida signals things. “Like Hook Up, Hold your brakes! Spill your flaps, Now fold your wings!”

YES Carrier life is something, dangerous and hard. Your wings will all turn green, and your ass will turn to lard. Oh take us back to “Dago”, and give us stateside duty. Where once a month we fly four hours, or maybe strop a beauty!!

Poem republished with the permission of Jane Allen, widow of Lt. Sanderson

Lt. John P. Sanderson was KIA

~ ~ ~ ~ ~

Eulogy for the October 21, 2012

USS Gambier Bay Memorial Service

By Rita Heinl, Widow of Charles (Charlie) Heinl

The Gambier Bay – VC10 was a big part of Charlie’s life. Before thereunions he never talked about the sinking of the Gambier Bay. From the days he, Tony, and Marty worked on getting a roster together – they met in Ohio or New York occasionally and compared different names and addresses they found. Charlie spent many hours in the eveningto locate names and addresses of members from telephone books that he remembered. These telephone books were given to him by members of our community who went on vacation and collected them at the different places where they visited. The first reunion in St. Louis, which was 25 years after the ship was sunk, was an experience. I never saw so many men shed a tear when they saw some of their former service men. At the one reunion in California when they distributed the book “The Men Of the Gambier Bay”, he had orders for 45 books for relatives and members of the Community, when you live in a small community like we do everyone knows everybody. He missed one reunion which was the second one in San Antonio, Texas. He was invited by a great nephew to San Diego, California at the same time. Our great nephew was in the Navy and was made Commander of a fleet of 70 helicopters at the Naval Base on Coronado Island. I thought it would be to much for me to keep up with things so our oldest granddaughter, Ashlee, Mark and Sandy’s daughter went with him. They stayed at the Naval Base on Coronado and by the time they left to come home all the Navy men were calling him “Uncle Charlie”. This was a great experience for him.

He enjoyed being secretary and treasurer for the Association and being involved with the many reunions. There is a time when things change and the next generation takes over. We wish them success in the years to come. We enjoyed all the reunions, have been in many states. We have met a lot of nice people and have many pleasant memories.

Charlie Heinl crossed the bar in December 2011

~ ~ ~ ~ ~

In Memory of the Brave Men of the USS Gambier Bay

October 21, 2012

By Mark Heinl and Ashlee Heinl-Botkin

Son and Grandaughter of Charles (Charlie) Heinl

First I would like to say that I am honored to speak on behalf of all of those that we are here to honor today. Each year, I am humbled by the presence of the men of the USS Gambier Bay, those survivors that have earned the respect of each and every city they have visited over the years. It was just a year ago that my wife and I had the distinct privilege of bringing my Dad to what would be his last Gambier Bay reunion. The Gambier Bay was such a huge part of my Dad’s life, it seems only fitting that I carry on his legacy by sharing a few things with all of you. Thursday, the 25th, will mark 68 years since the Gambier Bay was lost to sea. Yamato had attacked and the USS Gambier Bay had been one of its victims. The Yamato may have won the battle that day, but even in their darkest hours, the men of the USS Gambier Bay held strong and stuck together and proved that their brotherhood was stronger than even the mighty ships of Japan. 85% of the men that were aboard the USS Gambier Bay survived what my Dad said was probably one of the most unequal battles of two ships that had ever been fought. The tiny little Gambier Bay versus the mammoth Yamato, the ship sunk but the men were lifted by their own strength and the never-ending will to live. Most of us cannot even imagine the experiences these men had during their 45 hours in the water. The fear that they must have felt as the Japanese ships cruised by and videotaped them floating as if they were merely a form of entertainment, is a fear that I wouldn’t wish on anyone. There were sharks that killed and consumed their brothers’ right before their eyes. These men are and were heroes who have paid far too great a sacrifice.

The USS Gambier Bay reunions began to commemorate the 25th year in 1969 in St. Louis Missouri. I was nine years old. Since then the reunion has traveled back and forth all around the United States. Each city we meet presents us with a new opportunity to explore the beautiful country that our heroes fought for. This year we have had the chance to explore Milwaukee, Wisconsin, a place that we last visited in 1989. Mr. Steven Ponto serves as the mayor of Brookfield, but also shares something great in common with myself and some of you in this room. His father was aboard the USS St Lo which also saw its demise October 25th in the year 1944. It is an honor to be respected so greatly in such a fine city. Thank you for having us and thank you for the wonderful experiences that we have shared here in the Milwaukee and Brookfield area.

Please let us take a moment to honor all of those men who paid the ultimate sacrifice whether aboard the ship or out in the ocean. Their heroism rings the same. 122 men were lost on that fateful day at sea. This year we learned of the passing of Wayne Galey who died in October of 2004, Ralph Wilderman who died March 3rd of 2006, George Howard who died July 14th of 2009, Leonard Jay Thompson who died March 17th of 2010, Franklin A Engel who died July 17th of 2011, Jack Turner who died September 7th of 2011, Jesse E. Lee who died September 13th 2011 and Jacob “Thorny” Thorwell who died October 11th of 2011. Our brothers who have passed since the last time we met are Fred Harry Eelman who died on October 28th 2011, My Dad and hero Charles G Heinl who died on December the 19th 2011, Don Heric who died a day later on December 20th 2011, Carl R. Duqiuette who died January 1st 2012, Roy Cowan who died February 23rd 2012, Paul Bennett who died February 28th 2012, Louis Vilmer Jr. who died March 24th 2012, Reverend John Goforth who died May 3rd 2012, Clifford A. Wood who also died in May of 2012, Charles Warren Schlichter who died June 3rd of 2012, and James R. Sherrod who died June 5th of 2012. May all of their souls rest in peace and may their USS Gambier Bay reunion in heaven be as elaborate as they all deserve! It is their memory that brings us here today. These men symbolize the great in America. Few will leave a legacy like the men of the USS Gambier Bay. Such a unique and wonderful group of men that deserve all the respect and admiration that this nation can present to them.

That October day forever changed all of our lives. Whether the child of a survivor who was raised to understand that the sacrifice that these men made would forever shape who we are as strong and thankful individuals. Or military personnel who live under the same oath and are prepared to make those same sacrifices that their brothers and sisters before them have made. Or the spouse of one of these brave seamen who lived with a lifetime of stories and experiences. Or even those of you who made your way here today to honor and pay tribute to men that you were never fortunate enough to know. The fight in us, the strong will in us, the courage in us, and most of all, the AMERICAN in us is because of these men.

Thank you for your attendance. Thank you for your support. My heart swells at the opportunity to honor my Dad and one of the most important things in his life. The USS Gambier Bay and its men and memories will live on for decades through the stories and experiences that have been shared. As the reunions continue, let us never forget the reason we are here and the men that we are honored to celebrate.

~ ~ ~ ~ ~

The Next Generation

By John Hagerty (son of survivor Ed Hagerty)

There it was, down in the basement: an old framed black and white photo of a navy ship. Growing up, that framed photo never elicited much curiosity within me. It hung on the wall, a memory to which I had little knowledge and felt no connection. I wasn’t even clear what type of ship it was. To my young eyes, the angle of the flight deck sort of looked like a big gun.

Oh sure, I was aware that my father served on a navy ship in the war. I had heard that he was the guy who drove the ship (since I didn’t know what a helmsman was, I figured the guy turning that big wheel in the bridge must be “driving” the ship). But as a youngster I asked few questions and he volunteered little information.

Looking back, I now recognize the hints my father dropped that something remarkable had happened on that odd-looking ship in the fading photograph. I remember he once described the “whooshing” sound made by the massive shells fired by naval guns as they screamed towards their target, getting louder and louder. I was too young to wonder how he would know of such a thing. I was horrified when he once remarked that some of the guys who jumped off the ship forgot to take off their helmets, thus breaking their necks when they hit the surface. “Why would they jump off the ship?” I wondered to myself. But I didn’t ask and he didn’t elaborate.

I don’t remember the first time I read of the Battle of Leyte Gulf. Unfortunately, the name doesn’t resonate in American history like Midway or Gettysburg or Yorktown. The battle with its four very separate engagements is too confusing and has too many varied elements to stir the soul of the casual history reader. That is a shame, because the amazing fight of Taffy III against utterly hopeless odds is one of the most remarkable stories in American military history.

I was in grade school when my father packed all of us (mom and six young kids) into the station wagon and drove halfway across the country to Annapolis for the USS Gambier Bay & VC-10 reunion. I was too young to glean the full significance of this group of men and the bond that pulled them together. They all seemed to be about the age of my pals’ parents. I didn’t pay attention to their talk. I didn’t understand. I wanted to see the ocean.

Finally, as a junior high student, I read Herman Wouk’s War and Remembrance, with its superb account of the Battle of Leyte Gulf. Now the pieces fell in place. As I read other military accounts of the battle, a picture of what my father went through, along with those guys I had met at the reunion, emerged. It was heroic and horrific – the sort of thing that happened to John Wayne and Robert Mitchum in the movies, not regular folks like my dad and his buddies that I had met in Annapolis.

I’m not sure why, but the more I learned about the battle and the heroic death of the Gambier Bay, the more I figured I should not ask my father about it, thus forcing him to relive the horror. Instead I asked my grandmother. She, of course, had been forced to wait those agonizing days after the ship went down, not knowing if her 19-year-old son had gone down with it. When they were finally reunited, the excited young man poured out to his mom the entire story of the battle, the sight of enemy warships pouring horribly destructive shells onto his ship, the death of the tiny carrier and those harrowing days spent in the water with his fellow survivors. My grandmother had been anxiously waiting for the day when I would ask what happened. She related the story with images and details that I never heard from my father. As I listened, the horror and amazement that I felt was mixed with something else: pride.

With each passing year there are fewer and fewer people left to tell the remarkable story of the USS Gambier Bay. We are incredibly fortunate that the sailors and airmen who survived the ordeal have taken major steps to preserve the memory. Certainly, the rest of us can never fully grasp the bond forged by battle, survival, and ultimately, victory. They carry that bond to the grave.

Unlike that photo in the basement as I was growing up, the story of the final battle of the Gambier Bay is one that should never be allowed to fade. The men who were there have done their part, and may of them continue to do so. But now it is time for those of us in the “second generation” to climb aboard and report to our stations. There is much that can and should be done to preserve the memory of the gallant fight waged by the Gambier Bay against hopeless odds. Like The Charge of the Light Brigade, it is a story that can not help but stir the soul and arouse the deepest pride.

I encourage every member of the “second generation” of Gambier Bay and VC-10 survivors, as well as anyone who appreciates the amazing thing they did on a gray, rainy day in late October of 1944, to join the USS Gambier Bay (CVE-73) & Composite Squadron VC-10 Association. Volunteer your talents to help keep alive the memory.

John’s father, Ed Hagerty, crossed the bar in June 2013

~ ~ ~ ~ ~

Sailor Survived a Sinking Ship/Carl Amundson Served Aboard USS Gambier Bay

By: Julie Buntjer, Worthington Daily Globe

CHANDLER – The USS Gambier Bay went down in history as the only American aircraft carrier to be sunk by gunfire during World War II. She remains at the bottom of the Pacific Ocean today, a victim of an Imperial Japanese Navy attack on October 25, 1944.

The USS Gambier Bay went down in history as the only American aircraft carrier to be sunk by gunfire during World War II. She remains at the bottom of the Pacific Ocean today, a victim of an Imperial Japanese Navy attack on

October 25, 1944.

More than 120 of the Gambier Bay’s sailors were killed in action, with another

208 wounded in battle. Still, an estimated 800 men survived — among them,

Carl “Whitey” Amundson of Chandler.

They floated for 44 hours at sea, the injured taking refuge in life rafts to avoid attracting sharks with a nose for iron-rich blood. Most of the men had donned life jackets before jumping overboard, and many sought out floater nets — large pieces of netting with floats interspersed through them.

Amundson was among 37 men who either sat on or held onto one of the floating nets. He also wore a life jacket.

They did all they could to remain awake, to stay safe from the sharks circling in the distance and to keep each other from going crazy until a patrol ship came to their rescue in the dark of night on October 27, 1944.

Their harrowing ordeal had finally ended.

Amundson’s story begins in southwest Minnesota. Born a few miles south of Hadley, he grew up in Woodstock and attended one year of high school in Pipestone before dropping out to go to work on the farm. In September 1942, at the age of 17, he went to Mankato and enlisted in the Navy.

With the U.S. Navy in short supply of manpower, Amundson spent just 21 days at boot camp in Green Bay, Wisconsin. Then, after nine days off to say his goodbyes to family and friends back at home, he boarded a train bound for Alameda Air Station in San Francisco, California. By November 1, 1942, he had arrived at Pearl Harbor, Hawaii.

During his days at Pearl Harbor, Amundson worked on salvage duty, removing ammunition and anything else they could save from the ships that were heavily damaged or sunk during the Japanese attack on December 7, 1941. Later, he would board an amphibious patrol destroyer (APD), built in 1918 and converted into a landing craft for World War II, that delivered Jimmy Roosevelt’s Raiders to the Solomon Islands on reconnaissance missions.

“We’d come back in eight or 10 days and try to pick ’em up and hope

they were still alive,” said Amundson. “They weren’t to contact anybody

if they could help it.”

While on one of their missions, the APD came across the USS Helena and the USS St. Louis. The Helena had been struck by a torpedo and sunk, but the St. Louis, while badly damaged, was escorted back to San Francisco for repairs. Amundson’s older brother Eddie was aboard the St. Louis at the time and, in fact, stayed with the ship during his entire military service, from 1941 through 1945.

Battle off Samar

When Amundson landed in San Francisco, he was given seven days leave before being sent to Astoria, Oregon, to help put the USS Gambier Bay into commission. Their work was complete on Decemer 28, 1943, and the Gambier Bay and its men headed to the South Pacific.

Amundson was a boatswain’s mate aboard the Gambier Bay. In addition to working the deck crew, he was a helmsman on the carrier — the one who steered the ship. He also was a hot shellman, catching the powder cans from the fired rounds of the 5-inch 38 and throwing them overboard.

The Gambier Bay was built for ground support, carrying a fleet of 30 planes — half of them fighters, the other half bombers.

“The planes would strafe or bomb — they weren’t made for combat,”

said Amundson.

All of them were sent into the sky on the morning of October 25, 1944, as the ship floated in the Pacific Ocean, off the coast of Samar. In what became known as the greatest naval battle ever fought, the U.S. fleet faced off against the Japanese over control of Leyte Gulf.

The Taffy 3 task force, made up of a few escort carriers and some destroyers, paled in comparison to the Japanese fleet that had snuck into the region undetected.

“We run into the biggest Japanese fleet ever assembled — the biggest battleship ever built — with 18-inch guns,” recalled Amundson. “They could shoot 30 miles, we could only shoot nine.”

Five U.S. ships were sunk in the battle — aircraft carriers the USS St. Lo and the USS Gambier Bay, and destroyers the USS Johnston, USS Samuel B. Roberts and the USS Hoel.

The Gambier Bay was awarded four battle stars during World War II. Also known as a CVE-73, it would eventually be referred to by its men as Combustible, Vulnerable and Expendable.

Despite the damage the Japanese did to the American fleet, they sustained numerous casualties as well. That may have fueled Japanese Admiral Takeo Kurita’s decision to turn his ships back toward home.

“He had already lost two battleships, a cruiser, and I don’t know how many destroyers,” said Amundson.

Also factoring into Admiral Kurita’s decision was perhaps the perception the American fleet was larger than it really was.

“We had seven of these little carriers and a bunch of destroyers — that’s all we had,” Amundson said.

Abandon ship

The USS Gambier Bay came under fire shortly before 7 a.m., but it wasn’t until the Japanese fired its 8-inch guns repeatedly on the Gambier Bay that the crew realized the ship wasn’t going to survive.

When the crew was ordered to abandon ship, Amundson jumped off the fantail where he had been stationed.

“We just crawled over the life line and jumped,” he said.

At 9:07 a.m., the Gambier Bay capsized and sank, leaving her men floating in life jackets, floater nets and a smattering of life rafts.

“We figured we’d get picked up real quick, but the battle was going on at Leyte, and McArthur didn’t send anyone out to look for us until two days later,” Amundson said.

By then, some men “went crazy” drinking salt water, and others claimed they could swim to an imaginary shoreline. Most likely, the swimmers became food for the sharks that were seen circling in the distance.

Amundson shared a floater net with 37 other men, including a black man who was their mess cook. The cook had a knife with him and every time he saw a shark getting close to the net, he would stab the knife in the water and, at the same time, “I swear up and down he turned white.”

Finally, on October 27, a patrol craft came to their rescue, picking up about

80 to 100 of the men, including Amundson.

“We actually thought it was a Japanese destroyer that was picking us up,” he shared. “If we’d been out there much longer, we would have been on a

Japanese-infested island. The current was taking us toward one.”

Once they were safely on board, the first thing on their minds was getting food.

“I remember we ate everything they had on that ship,” he said.

They also ran out of coffee before arriving on Leyte.

The sailors aboard the sunken ships of the Taffy 3 were taken to New Guinea and eventually on to Brisbane, Australia, where they got a ride on a former luxury ship, the Loraline. The men arrived back in San Francisco on December 1, 1944, and were granted a 30-day survivor leave.

After the War

After Amundson’s survivor leave to southwest Minnesota, he returned to

San Francisco for his transfer to Portland, Oregon. There, he was assigned to the USS Fair, though he never left port on the ship.

Instead, he was sent back to California, this time to Port Hueneme, where he was assigned to the USS Gunston Hall, an LSD-5 landing ship.

“We ran up and down the coast with that, hauling landing craft from Long Beach to Port Hueneme,” said Amundson.

Nearing the end of his tour of duty, he was pulled from the ship and returned to Minnesota and honorably discharged from Wold Chamberlain Air Base on

June 17, 1946, his 21st birthday.

Amundson returned to his family home at Woodstock, but days later the family loaded up a school bus and headed back to California.

Though some of his family returned to Minnesota, Amundson found work in defense plants after the war, and by 1946, had married Bernice Bladen, a native New Yorker. She had been a Rosie the Riveter, riveting wing tips on P-38’s during World War II.

The couple settled in the San Fernando Valley and remained there until Bernice’s death in 2002. In 2004, Amundson returned to southwest Minnesota and purchased a home in Chandler. He has a daughter living in Iona, and a son in Anchorage, Alaska, along with eight grandchildren and about a dozen

great-great-grandchildren.

~ ~ ~ ~ ~

Honor Flight Network

In June 2011, Aaron Shelsman, USS Gambier Bay survivor, had the privilege of participating in an Honor Flight out of Chicago. Below is a photo of Aaron at the World War II Memorial and next to his home state of Illinois. As you can see Aaron is proudly wearing his USS Gambier Bay/VC-10 cap.

The inaugural Honor Flight took place in May 2005 with six planes flying out of Springfield, Ohio and carrying twelve World War II veterans. In May 2008, Southwest Airlines was named the official commercial carrier of the Honor Flight Network. In 2010, Honor Flight has safely transported 22,149 veterans to see their memorial, AT NO COST TO THEM. With the continued support of our grateful Americans, Honor Flight will have transported more than 75,000 veterans of World War II, Korea, and Vietnam to see the memorials that were built to honor their sacrifice to keep this great nation free!

If you would like to find out more about submitting your application to be part of an upcoming Honor Flight in your area or you are interested in volunteering to be a guardian on a flight, please visit the Honor Flight website at www.honorflight.org.

~ ~ ~ ~ ~

Memorial Wall Plaque – National Museum of the Pacific War (Nimitz Museum)

Viewing the Memorial Wall is an impressive and poignant experience for museum visitors. More than 1000 plaques line the 100 year old limestone wall surrounding the Memorial Courtyard. Individuals, ships or units from all United States and Allied branches of service that served in the Pacific during WWII may be honored on the Memorial Wall.

Below is a survivors memorial wall plaque for Dean M. Moel

dedicated by his family

~ ~ ~ ~ ~

~ ~ ~ ~ ~

The Tale of Two CVE’s

Dr. Norman Loats, Vice President/USS Gambier Bay Association

Survivor of the USS Gambier Bay

“It was the best of times, it was the worst of times; yes, it was the epoch of belief.”

CVE-63-VC42, VC65 was laid down as USS Chopin Bay; renamed the USS Midway of 3 April 1943; renamed the USS St. Lo on 15 September 1944.

CVE-73-VC10 was laid down as ACV-73 Hull Number 19 December 1943 and named the USS Gambier Bay.

They journeyed and fought together at Saipan, Tinian, Eniwetok, Manus, and Palau and joined the 7th Fleet in September 1944 under the command of Admiral Kinkaid. In early October 1944, they became a part of Task Unit 77.4.3 known as Taffy III under the command of Admiral Sprague.

On about the 12th of October 1944, they departed Manus Harbor and headed for the Philippines, arriving there on 20 October. Americans had landed on the Leyte beaches, and the CVE’s 63 and 73 were there to provide air cover for the invasion, for Mac Arthur had returned.

On 21, 22, 23 October, things went rather smoothly and on 24 October, the Japanese made a major attack against the American in Leyte Gulf – the Battle of Surigao Strait had begun and our pilots were put on alert.

October 25, 1944 and the call to General Corders at 0430. At 0630, we were secured from general Quarters, but only to be called back at 0644 – hardly time for coffee and breakfast. Dawn was at 0627, no sunrise. It was a misty morning, gray and overcast.

About the same time, Yamato’s look outs, more than 150 feet high in the crow’s nest and able to see 20 miles, cried out “masts on the horizon” – not just masts, but the shapes and silhouettes of aircraft carriers. They couldn’t believe that we would be foolish enough to come within the range of Yamato’s guns.

Admiral Kurita was convinced they had stumbled upon one of Halsey’s carrier groups. Little did he know he had run into “The Little Giants.” Kurita sends a message to his headquarters: “By heaven sent opportunity, like a gift from the gods, we are dashing to attach the enemy carriers, our first objective is to destroy the flight decks, and then the task force.

About the same time, our patrol pilots radioed, “Enemy surface Force – 4 battleships, 8 cruisers, and 11 destroyers 20 miles northwest closing in at 30 knots, pagoda masks, the largest red meatball flag I’ve ever seen flying over the largest battleship I’ve ever seen.”

Taffy III with its 6 CVE’s, 4 destroyers escorts, and 3 destroyers had encountered the Centre Force of the Japanese Navy under the command of Admiral Kurita. It was their 18” guns vs. our 5” guns, but we had our pilots and their bombs and our Escorts with their torpedoes. Admiral Sprague had ordered the launch of our aircraft.

The Battle off Samar was now on.

October 25 was fittingly the anniversary day of the Battle of Balaclava (1854) in the Crimean War, memorialized in Tennyson’s poem, “The Charge of the Light Brigade.” It was also St Crispin’s Day, but there was no King Henry to inspire. “We few, we happy few, we band of brothers for he today that sheds his blood with me shall be my brother.” There were many brothers during the next 2-1/2 hours. With much courage and sacrifice.

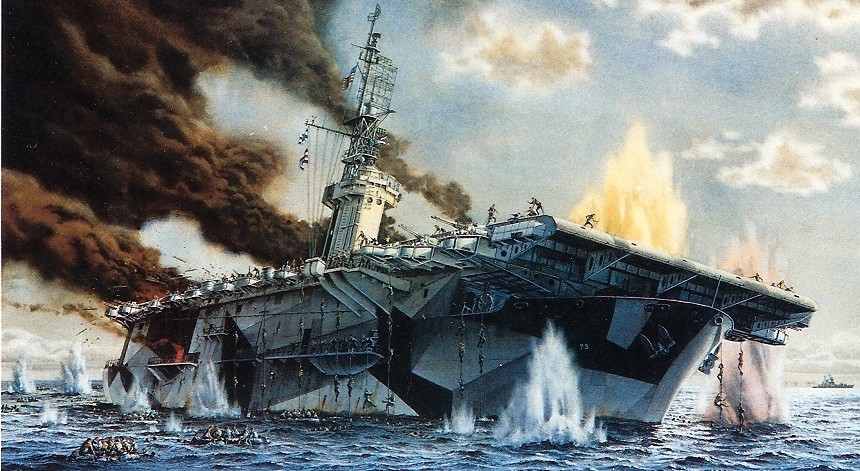

They are shooting in Technicolor, “one sailor shouted as the great geysers of colored water were marching very close to the CVE-73 USS Gambier Bay. At approximately 0810, they found the range and set fire to the aft flight deck, and about 10 minutes later an 8” shell exploded in the forward engine room – she was now defenseless, 3 other cruisers join in for the kill. The USG Gambier Bay is hit every other minute for the next hour, and at approximately 0850 abandon ship was ordered, and shortly after 0900, it was sunk and out of sight. For the survivors, the next few days would be a bitter challenge.

The constant assault by our carrier borne aircraft, their relentless pursuit with their bombs and guns, and the determination, courage and accuracy of our Escorts with their torpedoes were taking its toll on Admiral Kurita’s ships, and no doubt weighed heavily in his decision to regroup.

They were soon to learn of Taffy III’s audacious resistance, the effectiveness of which no tactician could ever have foreseen, and no statistician could have measured.

Kurita wasn’t sure how the battle was progressing or what they were truly up against, and he really thought he had been tricked into a trap. Between the battle of 24 October and now this battle, he had already lost half of his fleet. In the last two hours, he had 4 cruisers so badly damaged that they had to drop out of the battle. He faced the real prospect that if he continued this running battle, perhaps none of his warships would return home.

Therefore, at approximately 0930, 25 October 1944, Admiral Kurita gave the order for the fleet to reassemble around Yamato; they then headed north away from Taffy III and away from Leyte Gulf as well. The mighty Centre Force was going home.

Admiral Sprague could not believe what he was seeing. At the beginning of the Battle, he feared he would make history by being the Commander of the first carriers ever destroyed by naval gunfire, now he was making history as the victor in the most unlikely win in U.S. Naval history.

Around 10 am, the carrier group of Taffy III still celebrating its narrow escape from Kurita’s gunships, and having been at General Quarters for 3 hours, they were wrung out and giddy over their good luck. The men of CVE-63 USS St. Lo had been given a condition one easy allowing half of the crew to stand down from general quarters and get a cup of coffee.

However, this was short lived. Shortly before 11oo, Taffy III came under the wholesale Kamikaze attack. The Japanese Army Air Corp had debuted this horrific new mode of warfare earlier that morning.

Few men aboard the St. Lo saw the plane hit their ship – for half the crew was still enjoying a breather. The zero fighter with a bomb under each wing plunged into the flight deck. This set off a series of terrific explosions, shattering several planes, blowing hangar doors from their hinges, setting several planes on fire, and throwing men overboard. After several more of these powerful explosions, the ship was ripped apart, and thus the order to abandon ship. She was gone in 29 minutes.

The Survivors of CVE-63 USS St. Lo were picked up by our Escorts during the next couple of hours. The cost of life was dear.

The survivors of CVE-73 USS Gambier Bay were now forming groups of various sizes along with the other survivors of the Hoel, Johnston and Samuel B. Roberts.

The sport where the USS Gambier Bay was sunk, the ocean is about 7 miles deep. The waters are warm, but after dark, it is cold enough to give you hypothermia. The badly wounded were paced on rafts and/or floater nets along with some officers. The rest were floating in their “Mae West” Kapoks and CO2 life belts.

Shortly after noon on October 25, an avenger torpedo plane flew low overhead and dipped its wings. We now felt for sure it wouldn’t be too long before help would be on its way.

We had no food or water, and not having drinking water would soon become a serious problem. By mid-afternoon, the sharks had made their appearance. Thank God they never attached the group at large. At night was beginning to fall, we started to shiver and some began to pray. A ship approached, and we began to shout and yell, but then we realized it was a Japanese destroyer laden with men from a sunken Japanese cruiser. It came within a 100 years of us. They did not open fire on us.

As the first night deepened, optimism of a quick rescue was turning into discouragement. But there was still hope, and to keep our spirits up, we sang some songs – “Deep in the Heart of Texas,” I’ve Been Working on the Railroad,” etc.

But much suffering had been endured, and thus the singing didn’t last very long. We also wondered what had happened to our shipmates.

The random strikes by the sharks terrified us through the night. Exhaustion was taking its toll. Men would fall asleep; drift off, never to be seen again. The night seemed to last forever.

Morning of the second day – surely they would find us and rescue us soon. Still no food or water. We looked around the horizon – nothing. The Kapoks were beginning to lose their buoyancy. Most of us, however also had our CO2 life belts and thus could stay afloat. Thirst was a serious problem. Those who drank the sea water often became delirious. Some would say they were going for a beer, others stated they were swimming ashore, and others would see their relatives waving at them. They would disappear never to be seen again.

The second day was bright, clear, and hot. By noon most suffered from sunburn, and the sharks were feeding on the stragglers. Mid-day, we again saw planes overhead, but they gave no indication of seeing us.

Admiral Barbey’s rescue ships reached the point where survivors reportedly had been seen on the day of the sinking, but he was actually 30 miles south of where we had sunk. He then observed the current moving toward Samar, and they began working south and west. At 1500 that afternoon, they spotted a survivor, but he was a Japanese pilot who had been shot down and know nothing about the survivors of the USS Gambier Bay.

After another day of riding the swells, exhaustion set in. Even the alert began nodding off to sleep, and their fatigue deepened. The comfort of the tropical waters was like morphine, a great way to a gentle death.

By the second night it was every man for himself. The conversation and prayers died away. Many men didn’t look like men anymore. They were raw with sunburn, their lips were grotesquely swollen and blistered, and their eyes were bloodshot, dead and haunted.

Many had given up hope of a rescue. Those in my group, the floaters that is, tied ourselves together with our shirttails so we wouldn’t drift away, because if you did, you were gone and became shart bait.

October 27, early morning, a miracle occurred. We saw a small ship on the horizon and they were friendly. They were LCI’s sent out by the 7th Fleet. We had been rescued! At noon on 27 October, Commander Baxter decided that all survivors in the area had been rescued and set course of the Little Fleet for San Pedro on Leyte (one small group was not rescued at that time and were picked up some time later – they ended up spending 72 hours – only one had survived).

At approximately 0100 28 October, we entered San Pedro Bay, and the survivors were taken off either to go aboard a Hospital Ship, a Transport or an LST for movement toward the U.S. via Australia, setting foot on U.S. soil early December 1944.

Thus the Battle off Samar was over. It is estimated that 670 men went down with their Taffy III sips and some 116 men died at sea from the elements, wounds and sharks. Of these numbers, 131 were from the USS Gambier Bay and 126 from the USS St. Lo.

It has been referred to as the greatest of all Sea Battles, or as the greatest naval battle ever fought, or the last large-scale engagement between opposing navies that the world will ever see. Refusing to strike our colors and admit defeat, we reflected U.S. Naval traditions at the epitome of its finest hour.

And the last sentence of our Presidential Unit Citation:

“The courageous determination and the superb teamwork of the officers and men who fought the embarked planes and who manned the ships of Task Unit 77.4.3 were instrumental in effecting the retirement of a hostile force threatening our Leyte invasion operations and were in keeping with the highest traditions of the United States Naval Services.”

The Battle off Samar was a battle of firsts. The first time a U.S. Aircraft carrier was destroyed by surface gunfire, the first time a U.S. ship was sunk by a suicide plane, and the first time the mightiest Battleship afloat fired on enemy warships.

May we never forget those who made and those who are making the supreme sacrifice so that we may continue to enjoy our liberties and freedom. Yes, here aer the brave and here is their place of honor. Our shipmates gave their today so that we could have our tomorrow. May that tomorrow embrace the beauty of being, may that tomorrow provide time to see the vest in each other, may that tomorrow be filled with kindness, love and understanding, may that tomorrow provide us the time to enjoy the beauty of America.

Yes, ”It was the best of times, it was the worst of times.”

~ ~ ~ ~ ~

A Sailor’s Prayer

We will not go gently into this dark night, For the love we carry will guide the light, And hold our tears ‘til the morning’s bright. Awakened again into the night, We will not go gently into this dark night, The day surrounds us without its light, And silence falls, come soon the night. Where shadows cast past fire’s light, We will not go gently into this dark night, The paths before us, the dark, the light, We ask for nothing, we know what’s right. The truth, the glory, it’s found its fight, Our strength, our courage, our guiding light, We will not go gently into this dark night, And give our life without the right. To call the sun into the night, And question the question, what’s wrong, what’s right, We will not go gently into this dark night. For the love we hare will guide the light, And pray someday you find what’s right? We pray someday you find the light, We will not go gently into this great night. The paths before us, the dark, the light, Tomorrow comes and so the fight, Where Heroes fall but still we fight, Their voices call into the night, This war won’t end, no end in sight. We ask for nothing, we fight this fight, We ask for nothing, we know what’s right, We ask for nothing, We found the light.

* * * * *

Joseph Anthony Welteroth, US Navy/Winter 1945, Pacific Ocean

Dedicated to those who have served and are serving our great nation – published by the sons of Joseph Anthony Welteroth in the NY Times –

Joseph, Michael, Gregory, and Jacob

~ ~ ~ ~ ~

POW/MIA Remembrance Table

There is a Table, which is set with circular proportions, symbolizing our intent, our unending desire to know and to understand, and believe that our missing guest will someday be present – REMEMBER!

This Table set for one is small, symbolizing the frailty of one prisoner along against his oppressors – REMEMBER!

The single Red Rose displayed is sheathed with barbed thorns signifying the blood our comrades-in-army may have shed to ensure the freedom of our beloved United States of America. The rose also reminds us of the families and friends of our loved ones who keep the faith awaiting their return – REMEMBER!

The Yellow Ribbon tied so prominently on the vase is reminiscent of the yellow ribbon worn by those who bear witness to their unyielding determination to demand a proper account for our missing – REMEMBER!

The Candle is lit reminiscent of the light of hope, which lives in our hearts to illuminate their way home, away from their captors to open arms of a grateful nation – REMEMBER!

A Slice of Lemon is on the bread plate to remind us of their bitter

fate – REMEMBER!

There is Salt sprinkled upon the bread plate reminding us of the countless fallen tears of families as they wait – REMEMBER!

The Glass is inverted, they cannot toast with us this night – REMEMBER!

The Bible rests on the table offering us strength gained through faith, and reminding us of our country’s roots – REMEMBER!

The Chair is empty, they are not here – REMEMBER!

All of you who served with them and called them comrades; who depended upon their might and aid, and relied upon them, for surely, they have not forsaken you – REMEMBER!

REMEMBER! – until the day they come home – REMEMBER!

~ ~ ~ ~ ~

Remembering Gambier Bay Juneau Residents

Travel to Gambier Bay to Celebrate the 65th Anniversary

of Sinking of Namesake Vessel

Posted: Sunday, December 6, 2009 – By: Kathy Koklhorst Ruddy

“We recognize your sacrifice” – these are the words we spoke as we read the names of the 129 sailors and aviators who died in the sinking of the U.S.S. Gambier Bay at the Battle of Samar, in the Philippines, during World War II.

We spoke these words 65 years ago to the day of the sinking.

We were a group of seven, traveling to Gambier Bay, an expansive and gorgeous bay south of Juneau, on October 25, the 65th anniversary of the sinking of the namesake vessel in 1944.

Twenty-four bays in Southeast Alaska provided names for World War II aircraft carriers.

The U.S.S. Gambier Bay was one of the group of vessels known as Taffy 3 critical in turning the tide against the Japanese Center Fleet, which was advancing on the virtually undefended 700 Allied ships, with 190,000 troops aboard, ready and waiting to invade the Philippines to drive out the occupying Japanese.

When my husband, Bill Ruddy, suggested this commemorative trip almost a year ago, I was skeptical, until I learned the significance of the Taffy 3 group’s resistance against overwhelming odds. I also learned, through my brother, that our father had been stationed on one of those 700 exposed ships.

These are the words of the commander of one of the Taffy 3 vessels, to his crew:

“This will be a fight against overwhelming odds from which survival cannot be expected. We will do what damage we can.”

Tim Armstrong, Past Commander of the American Legion Post 25 and of the VFW Post 5559, led the service. He read a citation from the American Legion and also from the Juneau Navy League. Armstrong is a life member of the Alaska Military Order of the Purple Heart, and Senior Vice Commander Disabled American Veterans Chapter 4.

Bill Ruddy, who served in the U.S. Army Reserve and Alaska Army National Guard for six years, played “Eternal Father Strong to Save” on the trumpet. A wreath was thrown into the waters of Gambier Bay to recognize the sacrifice.

We traveled on our boat, the Princeton Hall, the 65 foot boat built at Sheldon Jackson College in Sitka and launched three days before the bombs fell at Pearl Harbor December 7, 1941. The vessel was conscripted by the Navy to operate patrol in Southeast Alaska during the war, and returned to the Presbyterian Church at the end of the war. The boat passed into private ownership in the 1960s.

Cyril George, Salvation Army Corps Sargeant Major (retired), and former Mayor of Angoon for many years, participated in the ceremony and played “What a Friend We Have In Jesus” on the guitar. George, then a student at Sheldon Jackson College, helped build the Princeton Hall, working especially on the installation of the engine and the stack. He then served from 1942-44 in a war plant in New Jersey, fabricating materials including aluminum housings for radar equipment being newly manufactured.

Also participating in the ceremony were Harry James, Marine Corps active and reserve 1964-75, Vietnam veteran, and Alaska Army National Guard aviator 1976-2006, serving in Haiti, Kosovo, and Honduras; and Bob Herman, Vietnam veteran, Alaska Army National Guard 6 years, New York Air Guard 20 years, and Air Force Special Operations Rescue.

~ ~ ~ ~ ~

Lost at Sea

Before my mother passed away, she shared a box of family heirlooms with me. In it I found mementos of her brother Sonny, an uncle I had never known. After the bombing of Pearl Harbor, Edmond Truett “Sonny” Franklin, 18 joined the Navy. He first served on the USS Ralph Talbot, one of the few destroyers that survived the Pearl Harbor attack. In December 1943, Sonny was transferred to the USS Gambier Bay, a ship that was heading to the Leyte Gulf in the Philippine Sea. The Japanese, concerned about growing U.S. troop strength in the sea, planned a massive three-pronged attack against the U.S. ships there. Traveling at night, they were hoping to launch a surprise offensive. On Oct. 25, 1944, the battle began. The brave sailors of the Gambier Bay barely had time to launch any aircraft before the flight deck was destroyed. The next shells destroyed the engine room, then other vital sections of the ship. Eventually, the order came to abandon the sinking ship. Despite the severity of the attack, 727 of the 849 crew members of the Gambier Bay survived. Sadly, Sonny was not among them. A letter dated Dec. 19, 1944, from Capt. Walter V.R. Vieweg to my grandparents begins, “it is with deep sorrow that I write concerning your son, Edmond T. Franklin, WT2 c, USN, who following the sinking of the Gambier Bay on 25 October 1944 was reported missing in action.” Today, many Americans want to preserve the memories of their parents and grandparents during World War II, and my family is no exception. We designed a memorial to honor our lost hero, a shadow box containing a picture of Sonny in uniform with a photo of the Gambier Bay sinking and the Purple Heart the family received after Sonny’s death. The youngest Franklin boy Robert Houston Franklin, Sonny’s great-nephew, proudly displays it, keeping the memory alive for future generations.

Written by Jobeth Pilcher, niece of Edmond Truett “Sonny” Franklin

~ ~ ~ ~ ~

USS Gambier Bay survivor, Dr. Norm Loats interview with television station 12 in Tempe, Arizona for the stations “Hero Central” segment during the 2009 Reunion.

~ ~ ~ ~ ~

Hal Berven Local Veteran Recalls Service Aboard

Ship Built at Kaiser in Vancouver

Seventy years ago, workers at Vancouver’s Kaiser Shipyard watched as they saw the USS Gambier Bay take form.

Hal Berven had a different view of the aircraft carrier while treading water in the Pacific on October 25, 1944. He watched it disappear.

After being ordered to abandon ship, the wounded sailor swam away from the damaged aircraft carrier, and then he looked back at his sinking ship.

“I saw it turn over,” Berven said during an interview just west of his ship’s launch site. “Steam came up, and the ship was gone.

“I sensed a rumbling.” And then, the Vancouver veteran said, “I felt alone.”

But the Gambier Bay and its crew had done their jobs in the Battle of Leyte Gulf. They were part of a task force that turned back a much larger Japanese force opposing the Allied invasion of the Philippines.

The Gambier Bay was one of 14 Vancouver-built escort carriers that fought in what’s been called the biggest naval battle of World War II.

The USS St. Lo also was sunk in the Battle of Leyte Gulf, which included four different naval actions over the span of four days.

The Gambier Bay and St. Lo were among 50 carriers built during Vancouver’s WWII shipyard boom.

“They were in the thick of the battle,” said Bill Wheeler, professor emeritus of engineering at Clark College and retired Navy officer.

Five Vancouver-built carriers were lost due to torpedoes, kamikaze aircraft or enemy gunfire. Eleven were heavily damaged, Wheeler said, including 10 that were hit by kamikazes.

The “baby flattops” helped fill a huge gap in the U.S. arsenal. After losing four aircraft carriers early in the war, “We had three carriers left,” Wheeler said.

With no air cover for convoys crossing the Atlantic, German U-boats sank ships faster than we built them, said Wheeler, who discussed the Kaiser carriers at the Clark County Historical Museum in April.

Production was hitting its stride 70 years ago along the Columbia River. In 1943, Kaiser workers launched 25 escort carriers and started work on 12 others.

“Just 14 of our crew were killed in battle,” he said.

One of them was a buddy; he was killed while arming a plane for an attack, when a rocket he was holding went off.

Planes from the USS Gambier Bay also supported amphibious operations in the Pacific, including landings at Saipan and Peleliu.

Berven was an aviation machinist’s mate on the Gambier Bay. He described his job as a plane captain, the crewman who made sure an FM2 Wildcat fighter was ready for its mission.

On October 25, 1944, the Gambier Bay was assigned to Task Force 3 off Samar Island, in one of the four engagements that were part of the Battle of Leyte Gulf. “Taffy 3,” as it was nicknamed, included six escort carriers, three destroyers and four destroyer escorts.

Huge mismatch

It was an epic mismatch. The Japanese had four battleships, eight cruisers and 11 destroyers.

“They had the biggest battleship ever built, the Yamato. It weighed more than all of us put together,” Berven said. “It was rather hopeless.”

The Yamato had nine 18.1-inch main guns; each escort carrier had a 5-inch gun.

“They all could travel at 32 knots and our carriers’ top speed was 18 knots. They closed in quickly.”

The Gambier Bay’s commander was able to avoid the shells for a while, Berven said: “Our skipper would change course and the shells would hit where we had been.

“They got close enough to fire point-blank. Armor-piercing shells were going right through us. Then they sent shells that exploded on contact.

“We got all our planes off but one, a torpedo bomber on the hangar deck that was loaded with gas and a torpedo. A shell hit that plane. It blew me into the air.”

Two Days in the Water

He regained consciousness, and then Berven said he crawled out in time to hear the captain order the crew to abandon ship.

Berven spent two days in the water before a rescue ship arrived. He held on to the side of a life raft because there wasn’t enough room in the raft. Most of the life rafts went down with the ship.

“We had no water for two days. Several men died from drinking salt water,” Berven said. A couple of sailors were killed by sharks.

But Taffy 3 turned back the Japanese. Shells and torpedoes fired by the American destroyers and destroyer escorts knocked the Japanese off stride. Aircraft from Taffy 3’s escort carriers were reinforced by planes from Taffy 1 and Taffy 2, damaging or sinking several Japanese cruisers.

The Japanese thought they were facing a much more formidable U.S. force and didn’t press their attack.

“They could have sunk every one of our ships,” Berven said. “They left. I think they were afraid of us.”

In misjudging Taffy 3, the enemy commander also misjudged the baby flattops his forces had sunk, the Gambier Bay and St. Lo. The Japanese mistakenly thought they’d destroyed two of the Navy’s big aircraft carriers, Wheeler said.

Gallantry and Guts

Naval historian Samuel Eliot Morison, a two-time Pulitzer Prize winner, wrote: “In no engagement of its entire history has the United States Navy shown more gallantry, guts and gumption than in those two morning hours between 0730 and 0930 off Samar.”

The St. Lo, the other Vancouver-built escort carrier lost that day, was the first major warship to be sunk by kamikaze planes.

Navy veteran Hal Berven looks over a 1945 newspaper with a photograph of him, at the right, getting a Purple Heart for wounds received during the Battle of Leyte Gulf. Berven took part in an oral-history taping on July 18, 2013 at the veterans’ memorial mural, not far from where his aircraft carrier, the USS Gambier Bay, was built at Vancouver’s Kaiser Shipyard.

* * *

Excerpts from story by Tom Vogt, republished with his permission.

Photos by Troy Wayrynen / The Columbian Newspaper.

*

Kaiser Carrier Veteran Hal Berven Interview with

Tom Vogt, The Columbian Newspaper.

Hal Berven crossed the bar in August 2013, shortly after

the story and interview were published.

* * * * *

Eulogy by Gary Berven, Son of Hal Berven

There are those here that called him Harold, or Hal, or Dad, or Grandpa. Whatever name you used, you all knew the same man. A man of honor, a devout and loving husband, a forever role model to two sons, a heroic sailor, and a friend to the very end. There is not a soul here today that won’t forget his stories, his impeccable ethics, his patriotism, and most of all, his complete and perfect understanding of right and wrong. A conversation with my dad was one that always evoked a reaction; sometimes strong agreement, maybe a difference of opinion, and almost always laughter. Dad loved to laugh, and he always made others laugh. That was one of his many gifts. Karl and I learned from Dad that when you do something, there is only one way to do it, and that was the right way. Don’t take shortcuts, don’t look for the easy way.

This was most evident in the way he built things out of wood. He was not just a woodworker, he was an artist. And this reminds me of a moment in time that I will always remember with a smile. If you ever saw Dad’s shop, you knew that the man loved his tools and the projects that they created. One day I was in his shop with him, when I noticed a strange stack of wood in the corner. As I looked closer, I realized that they were bundles of tied-up pieces of cedar. Each piece was exactly the same length, wrapped with a perfect length of string, and tied with a perfect bow. With a smile on my face, I said, “Dad, what are those?” He had a sheepish look on his face as he said, “kindling”. In that moment, even as I was laughing, I realized that even when he made kindling, he made it as perfect as he could.

It didn’t take very long for Dad to make an impression on someone. This was so true while he worked at Bemis. He developed customers that would buy from him, even though they could buy for less money someone else. He gave his word and his customers knew that they were getting more than a product, they were getting Hal Berven. An example of his effect on people was shown to me when my daughter Karina and her husband Brennan and their two boys lived with us a year ago. Brennan came upstairs and asked me if it would be OK with me if he called my dad. I was a little puzzled as to the purpose but said “of course”. Brennan then explained that he needed to interview someone for a class that he was taking. Downstairs he went to make the call. 20 minutes later, Brennan came back upstairs. He was visibly upset, with tears in his eyes. Karina and I both were concerned and asked what was wrong. He said with trembling voice, “I have never met a man with such high values, high morals, and the knowledge of what is right and wrong”. That was my dad.

To those of you that were his friend, thank you for being here and showing your love and respect to our family. To those of you that were his neighbor, thank you for watching over him, visiting him, and filling his lonely hours. And to those of you that are his family, I love you all so much for loving him so much. You filled his heart to bursting. I believe his last wish was to have a 90th birthday party with his family and friends, and you were instrumental in making sure that his wish came true.

~ ~ ~ ~ ~

World War II Veteran Recalls Sinking of Ship in Pacific

By Larry Kinneer, State of the Heart Hospice

Note: It is our pleasure to reprint this story about Charles (Charlie) Heinl, a WWII vet currently receiving hospice services through State of the Heart Hospice. State of the Heart cares for families and patients in eastern Indiana and western Ohio who are confronting a life-limiting illness.

This hospice is a national partner of We Honor Veterans.

*

On January 4, 1944, Charles (Charlie) Heinl left his hometown of Minster, Ohio at age 17. Little did he know that 10 months later he would be involved in the tragic sinking of the ship he was aboard, the USS Gambier Bay, and he himself would survive 42 hours hanging onto a life raft in the Pacific.

It happened 67 years ago, and the memories are captured in Heinl’s story which is one of the personal accounts of that tragic ocean battle on October 25, 1944. Heinl’s ship, a small escort carrier, was attacked by Japan’s largest battleship, the Yamato. The ship, Heinl recalled, “was monstrous.”

Today, Heinl, 85, of Maria Stein, Ohio, is a State of the Heart Hospice patient and is considering attending the annual reunion of the estimated 800 men who survived the Japanese attack. More than 120 of the ship’s sailors were killed.

Time has taken its toll on the number of survivors. Whether he goes or not depends on his health and is somewhat “iffy” explained his wife Rita. An optimistic Heinl, responded, “There’s still a chance.” Family members have helped the couple attend in recent years. Heinl was one of the youngest men on the ship. (Charlie Heinl and his wife Rita attended the reunion of shipmates who survived the attack on the ship. Their son Mark and daughter-in-law Sandy escorted them on the trip to Omaha, Nebraska October 19-23, 2012. Of the approximately 800 who survived the sinking of the ship, only seven attended this year’s reunion. A touching memorial was held during the reunion. Charlie’s son Mark, who serves on the board for the survivor’s group, read aloud the names of those survivors and their spouses who have died in the past year. A single bell chimed after the reading of each name. For Charlie, attending the reunion was a wish he has had all summer).

Heinl recalled he “jumped” into the water as the ship was going down. For a day, he had no life jacket and hung perilously to a life raft with other sailors. “As we watched back, we saw the ship roll over on its hull and begin to sink bow first, exposing the screws. It then sank,” he explained in his personal account of the battle on a “survivor’s page” on the Internet story about the sinking of the USS Gambier Bay.

In his account, he tells of the six to eight foot swells of water and how he and others took turns hanging onto the raft. “The men began seeing sharks and I thought I saw them too. Someone close to me was attacked. As time went on the sharks became a real menace.”

It was not until six hours after the Gambier went down that orders were issued to conduct a search and rescue mission. Staying alert and being aware of hallucinations became a problem as Heinl and the others struggled to stay awake. On October 27, 1944, they were finally rescue by a US PC boat. “The men rescuing us said they couldn’t get us out of the water fast enough as there were a lot of sharks in the area.”

Heinl escaped with only minor injuries and was later discharged from the Navy. But, his connection with the USS Gambier Bay was not over. Heinl, just as others, never got to see his shipmates again after the sinking of the ship. They all went their separate ways on various Navy assignments. That fateful day, however, lived in their minds. Just as others, Heinl, spoke rarely of his narrow escape from death. His dark memories of that day remained buried.

However, the thought of seeing his shipmates again lingered with him. He and several others he had contacted spent nearly two years trying to reconnect with their shipmates. “He would find phone books and get phone books of various cities across the country from friends and search through them for names of the survivors,” his wife explained.

Then, one day in October, 25 years to the day that the USS Gambier Bay went down, the survivors gathered for a reunion. It was the first time they had seen one another since the ship was sunk.

“I have never seen so many men cry at one time,” said Mrs. Heinl. “Charlie had never talked of the sinking of the ship much until then. I think it helped them all to openly talk about what they all went through.”

Heinl became active in the group and served as president, treasurer and secretary. Today, his son Mark has taken his position on the board. The couple has another son, John. The couple said they appreciate their hospice services. “Everyone is very nice and helpful to us,” Heinl said.

To this day, Heinl feels lucky that he was not seriously hurt in that tragic ship sinking 67 years ago. “I am happy to be alive after that experience,” he said from his comfortable home where he and Rita have lived for the past 56 years.

State of the Heart Hospice is very pleased to be part of NHPCO’s We Honor Veterans initiative. Kelley Hall, education coordinator for State of the Heart said, “All hospices nationwide are serving veterans, but in many instances are not aware of the patient’s Armed Forces service. Our veterans have done everything asked of them in their mission to serve our country and now it’s our turn to proudly serve them. Now, it’s time for us to step up, acquire the necessary skills and fulfill our mission to serve these men and women with the dignity they deserve. State of the Heart Hospice is proud to be providing care to Mr. Heinl.”

*

The NHPCO launched the “We Honor Veterans” campaign as a collaborative effort with the nation’s VA Centers. The resources of We Honor Veterans focus on respectful inquiry, compassionate listening, and grateful acknowledgement, coupled with Veteran-centric education of health care staff caring for veterans.

~ ~ ~ ~ ~