Sailor Recalls Loss of Only US Carrier

By David Barber

David crossed the bar in December 2014

David crossed the bar in December 2014

~ ~ ~ ~ ~

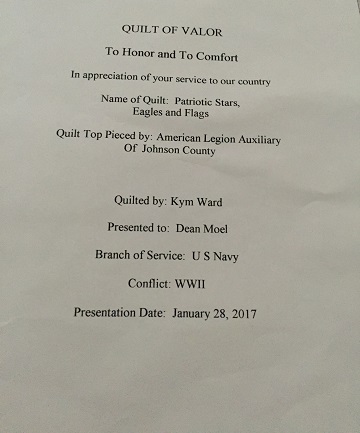

Quilt of Valor Presented to Dean Moel

by

American Legion Auxiliary of Johnson County

On January 28, 2017, Dean Moel was honored for his service in WWII with a Patriotic Stars, Eagles and Flags Quilt, which was quilted by Kym Ward

~ ~ ~ ~ ~

William Dailey Dugan

A Daughter’s Story

Wasn’t he so darn cute, my dad, William Dailey Dugan, who served on and survived the sinking of the USS Gambier Bay. He was running along the walkway (I don’t remember what he called it) with a group of other men, one his best friend, when he saw another sailor down. He stopped to help him while the others ran on. Seconds later a shell hit just ahead of him, causing him shrapnel injuries, but all those who had been running with him were killed. My Dad’s, typical selflessness, compassion and kindness in stopping to help a shipmate saved his life. He and others floated in the vast ocean for three long days, fighting off sharks drawn by blood in the water; watching others lose their senses from drinking sea water and delirium from injuries. He told of a sailor who was “out of his head”, letting go of the rope to go down to get something from his locker. The sailor disappeared under the water, never to resurface. Besides sharks, thirst, pain, and exposure, they lived in fear of a Japanese ship coming by and either killing them, or worse, taking them prisoner. Mercifully, the first ship to come by was a US destroyer (I belief, or maybe a U boat, I can’t remember, but couldn’t take them on, but they contacted a larger ship to rescue them. It would be more long hours of waiting before it finally arrived to free them from their watery prison. I’m so very proud of my late Dad (passed 1/22/2006), for his courage, but mostly for the man he was; ever gentle and kind and loving. A devoted, loving husband to my dear late mom and devoted, loving dad to his five children. He rests in peace at the national cemetery in Canonsburg, PA.

Story submitted by Cheryl Cunningham, daughter of William Dailey Dugan

William crossed the bar in January 2006

~ ~ ~ ~ ~

Cletus R. “Clete” Ring

PLAIN – Cletus R. “Clete” Ring left this world a better place than he found it on February 3, 2017. Just shy of his 91st birthday, he was born February 15, 1926, in Plain to Raymond and Emma (Blau) Ring.

Clete enlisted in the U.S. Navy during World War II at the age of 17. He served on board the USS Gambier Bay CVE73, serving as a motor machinist in the engine room. On October 25, 1944, during the Battle of Leyte Gulf, his ship was sunk by enemy gunfire. Wounded badly, Clete survived two days in shark infested waters, clinging to a life raft. He was subsequently awarded the Purple Heart.

Returning to Plain after the war, Clete married Anna M. Schmitz in August of 1947. Subsequently he built and ran the Skelly Service Station in Plain for over 20 years. He also was a member of the United Steamfitters Local 601. Following retirement Clete could most often be found at his sons’ business, RingBrothers, where he would keep staff and visitors regaled with his stories and advice to all, (and on all subjects).

Clete is survived by what he undoubtedly would say is his greatest legacy, his seven children, Steve (Nancy) Ring of Scottsdale, Ariz., June (Charlie) Drott of Scottsdale, Ariz., Gail Byrne of Madison (Tim Byrne of Middleton), Betty (John) Kraemer of Paradise Valley, Ariz., Karen (John) Heinz of Scottsdale, Ariz., Mike (Nancy) Ring of Plain and Jim (Peggy) Ring of Spring Green; 16 grandchildren; five great-grandchildren; six sisters, Caroline Weiss, Elvy Weiss, Bernice Weber, Alice Swinehart, Charlotte Dischler, Audray Gerber and a brother, John (Jack) Ring.

~ ~ ~ ~ ~

Clarence Harold Seever – Purple Heart

Date Unknown

Clarence crossed the bar in February 1996

~ ~ ~ ~ ~

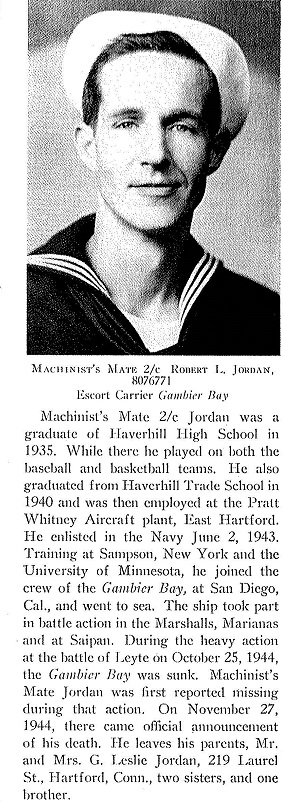

Robert L. Jordan – KIA

Robert was KIA

Robert was KIA

Article submitted by his niece, Carolyn Smith

~ ~ ~ ~ ~

Lage T. Naslund Story

By Val Benton (Descendent of Family Friend of Lage T. Naslund)

Greetings to the crew of the Gambier Bay and to their loved ones. I grew up in the tiny town of Malmo, Minnesota and on a recent visit there, I was chatting outside the general store with one of our “old-timers”, Gaylard Westerlund. Conversation had turned to our community’s Veterans when suddenly Gaylard remarked how tragic it was that Lage Naslund had “disappeared in WWII.

Since it is often my honor to read aloud the Veterans List at Memorial Day services, I was confused at hearing a war-related name with which I was unfamiliar. Upon further questioning, Gaylard related that he remembered Lage Naslund as being a friend of his older brother’s. He recalled that Lage had lived in Glory (a farm community just up the road from Malmo) and that he had served in WWII and never returned.

This story intrigued me as my grandmother’s family had homesteaded in Glory. The last of Grandma’s generation, my Great Aunt Vivian, was still living in a local nursing home– so on my next visit, I asked her if she knew anything about Lage Naslund. Her eyes lit up as she exclaimed, “Lage! I haven’t heard that name in years!”

It transpired that in 1930 Lage Torgny Naslund was an adventurous 19-year-old when he boarded a ship in Sweden and sailed to America searching for a new life. He settled in Glory next to my Grandmother’s home. He became friends with her family and often helped out on the farm. Aunt Viv recalled that she and her younger sister Eileen (just little girls at the time) would peek around the corner of the house to watch Lage washing his red hair in the rain barrel. They thought he was the “dreamiest thing” ever! My Aunt remembered that Lage had married a local girl named Signe Arvidson; that he had at some point gone off to war and never come back.

Lage and Signe – late 1930s

Wedding of Lage and Signe – 1933

I began scouring old family photos but was unable to locate one labelled “Lage”; I also was beginning to feel frustrated that no one could tell me what had actually happened to him during the war. That’s when I set out looking for Lage! My search took me to the local Historical Society, Veterans Office, churches/cemeteries and even the funeral home. Finally, I held in my hand an address for Barbara Kennedy, a niece to Lage and Signe Naslund. Unfortunately, the address I had been given was almost thirty years old…but it also was for a place I estimated to be not more than 10 miles from where I currently lived in Cloquet, MN.

I began scouring old family photos but was unable to locate one labelled “Lage”; I also was beginning to feel frustrated that no one could tell me what had actually happened to him during the war. That’s when I set out looking for Lage! My search took me to the local Historical Society, Veterans Office, churches/cemeteries and even the funeral home. Finally, I held in my hand an address for Barbara Kennedy, a niece to Lage and Signe Naslund. Unfortunately, the address I had been given was almost thirty years old…but it also was for a place I estimated to be not more than 10 miles from where I currently lived in Cloquet, MN.

So setting off on a whim and a prayer, I traversed a number of confusing country lanes until I located the house. Imagine my excitement when Barbara Kennedy answered my knock on the door! Tears filled her eyes when I asked her if Lage Naslund had been her uncle. She said how strange it was that I had come at a time when the family had recently been talking and reminiscing about him.

I learned from Barbara that Lage had married her Aunt Signe in 1933 and instantly become “the best uncle ever;” a favorite of family members old and young alike. He was a good-natured, happy man…full of laughter and life. One of her favorite memories was of him being such a strong swimmer, he could swim across the lake with two children on his back!

After their marriage, Lage and Signe farmed for a time locally before relocating to Minneapolis where he became a cement finisher. He took an Oath of US Citizenship in 1940 and went to Alaska to work on the ALCAN. He later enlisted in the Navy and was WT3c on the Gambier Bay when the ship was sunk in the Battle Off Samar. Lage’s widow Signe lived with her family during his absence, and niece Barbara recalls how heartbreakingly sad they all were to be notified after the battle that Lage was listed as MIA and later KIA. It was the only time she saw the adult males in her family openly cry. To this day, waves of grief wash over her when she thinks of that time in her childhood.

William Kennedy, Barbara’s husband, is a Veteran himself who did his master’s thesis on naval battles. By listening to him and reading literature he recommended, I have come to see how horrific was the Battle of the Gambier Bay and how heroic were the sailors who fought it. I feel overwhelming sadness at the thought that Lage (the incredible swimmer) was probably trapped in the depths of the ship with no chance for survival. But I’m glad today to have many pictures labelled “Lage” in my possession, and Barbara and I are working on a display of his photos/medals to hang in a local VFW.

Lage Torgny Naslund sailed on the Gambier Bay and lost his life in that terrible battle. He was a Swedish immigrant who loved America…enough to adopt her as his own country and to die in her service. I hope that in Heaven, Lage knows that he is still deeply loved and missed by his family and friends… and by a very, very grateful community.

Lage was KIA

~ ~ ~ ~ ~

Eugene Lewis

Date and Location Unknown

Eugene crossed the bar in August 1973

Photo submitted by his son, Bob Lewis and nephew Dave Lewis

~ ~ ~ ~ ~

Jack and Essie Pate

July 1947

Jack crossed the bar in June 1999

Essie passed in 1988

Photo submitted by his daughter Jennifer Pate

~ ~ ~ ~ ~

Forest and Evelyn Pruitt

Wedding Photo – March 1944

Forest was KIA

~ ~ ~ ~ ~

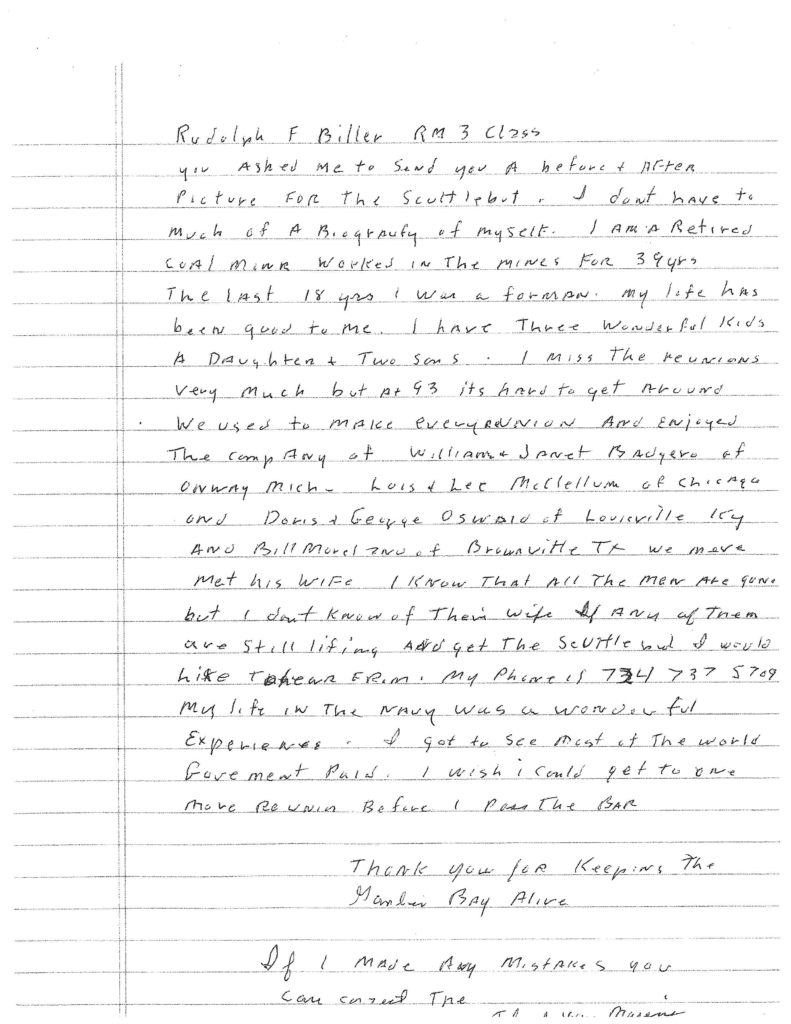

Rudolph Biller – December 2016

- Rudolph Biller

- Rudolph and his daughters dog – Freddie

* * *

~ ~ ~ ~ ~

August Robert Sankey and Family

Date Unknown

Left to right: daughter Kala, August, daughter Sharon, and son Kevin

August crossed the bar in January 2018

* * *

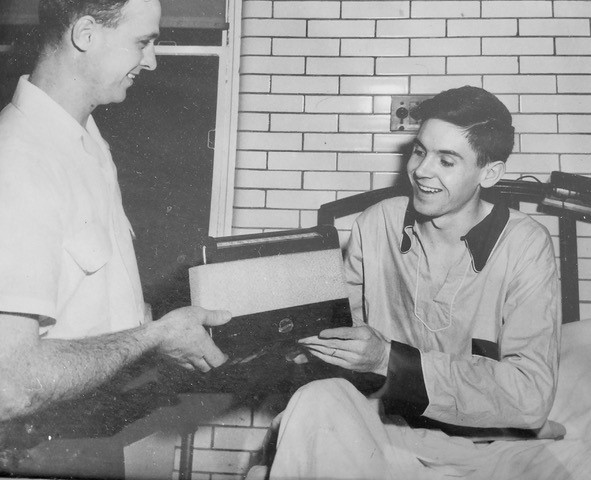

August Receiving a Radio in the Hospital After the USS Gambier Bay Had Sunk

1944

~ ~ ~ ~ ~

Joseph “Babe” Perone (Dates Unknown)

L to R: Joseph “Babe” Perone, unknown, Robert Bordt

L to R: Joseph “Babe” Perone, unknown, Robert Bordt

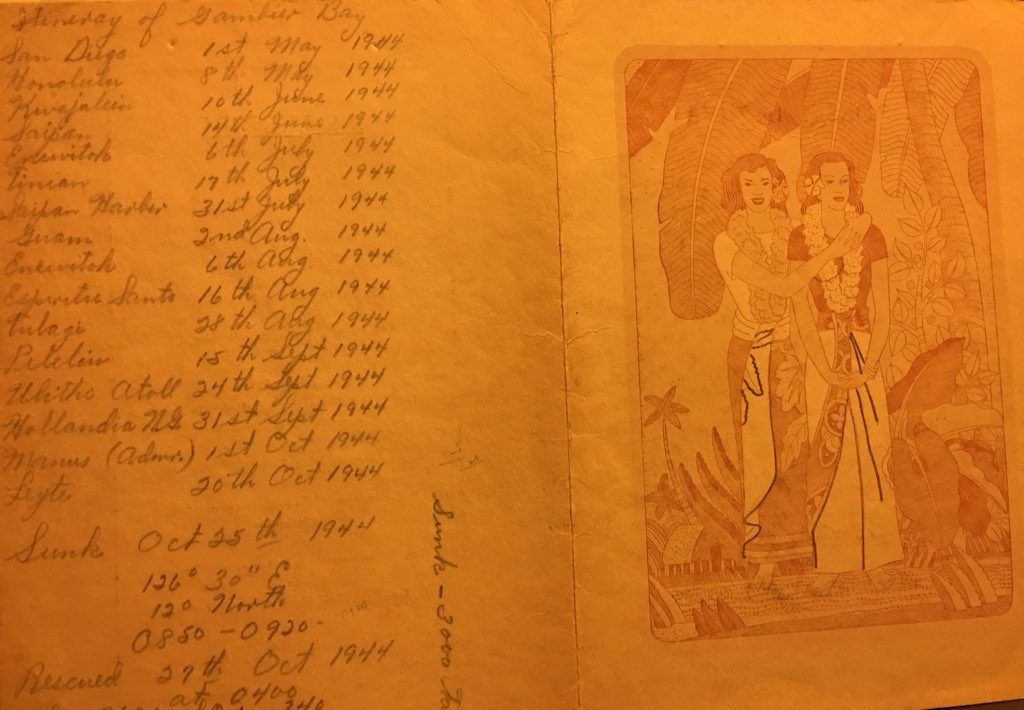

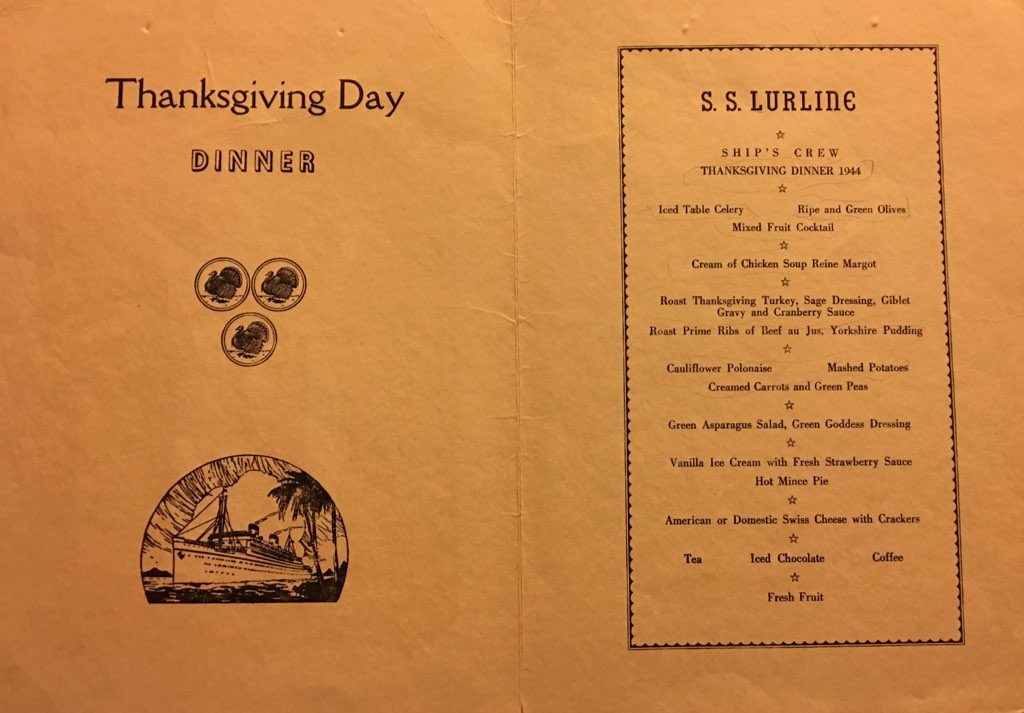

May 1 – October 27, 1944 – Itinerary

May 1 – October 27, 1944 – Itinerary Thanksgiving menu from the SS Lurline, the ship that picked up USS Gambier Bay survivors from the water

Thanksgiving menu from the SS Lurline, the ship that picked up USS Gambier Bay survivors from the water

* * *

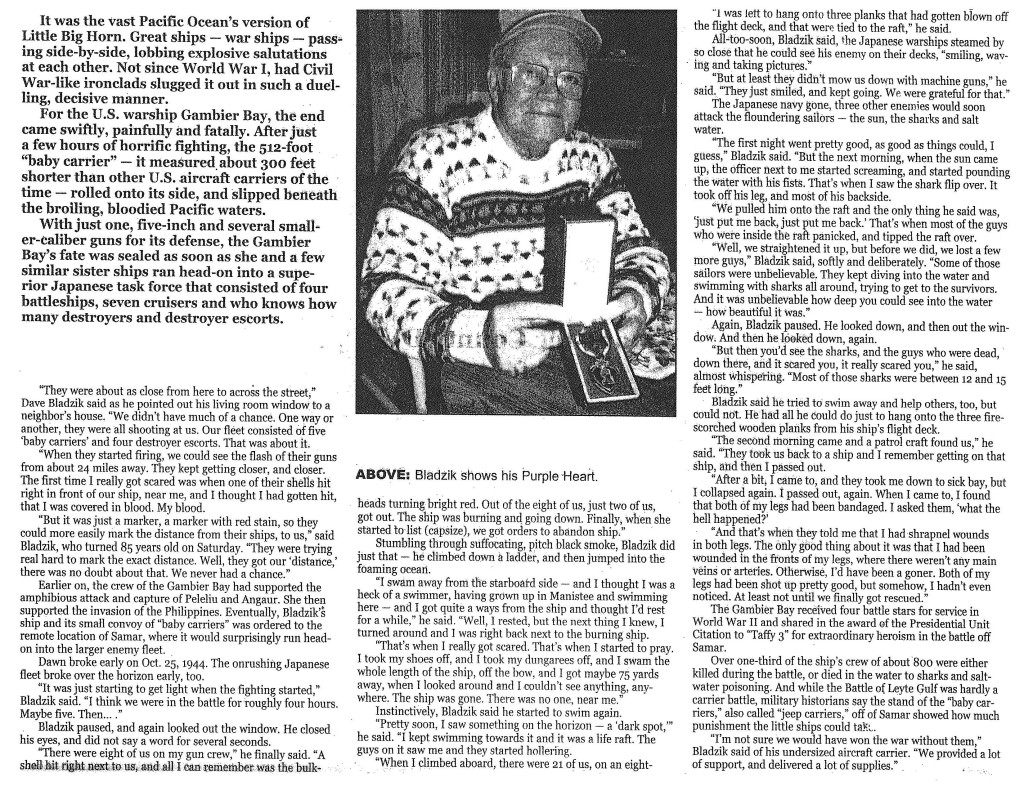

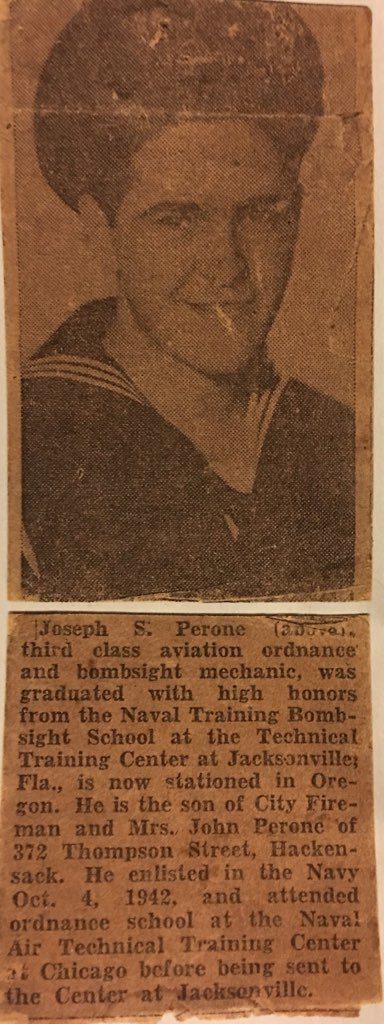

Newspaper Article

Graduation from the Naval Training Bombsight School

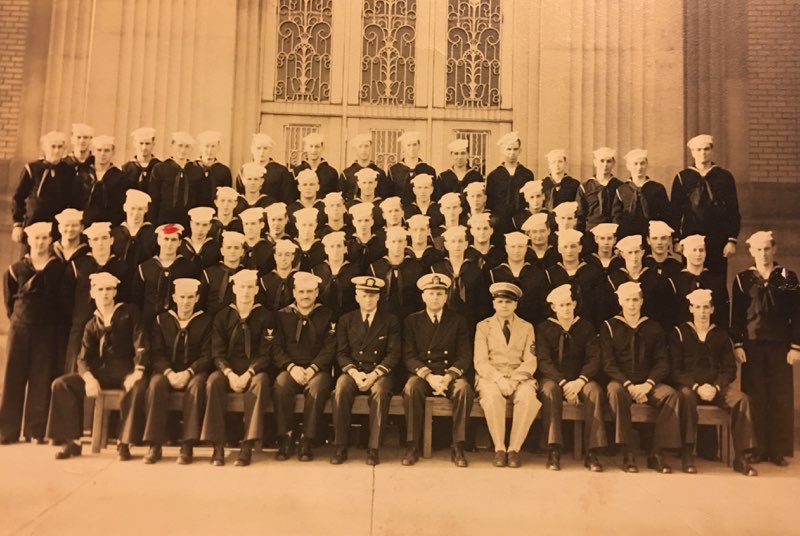

Joseph is the one with the red mark on his sailor cap

Joseph is the one with the red mark on his sailor cap

Joseph crossed the bar in January 1982

Photos were submitted by his son, Robert Perone

~ ~ ~ ~ ~

George and Gail Legath

1946

~ ~ ~ ~ ~

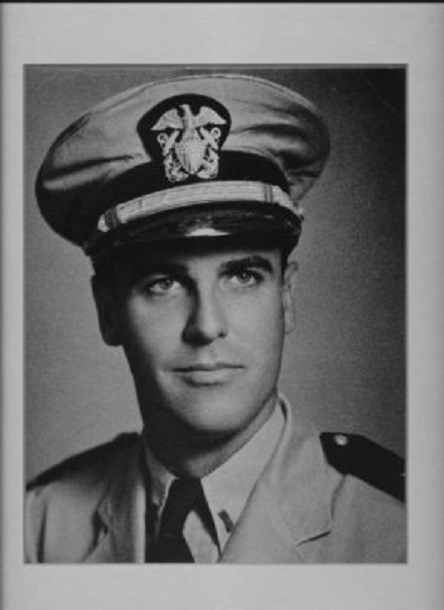

Lt. Robert G. Young’s Gambier Bay Story

Introduction by Philip R. Young, Son of Survivor, Robert G. Young

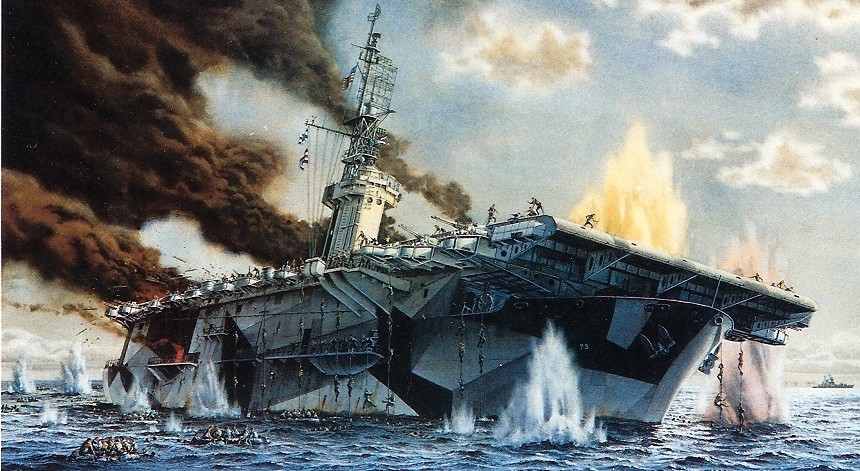

Lt. Robert G. Young served on the USS Gambier Bay, which was sunk by the Japanese armada off Samar Island in the Philippines during the Battle of Leyte Gulf which historians have described as the largest naval engagement ever fought.

In a letter home dated October 2,1944, Lt. Young wrote “I am on a carrier, which is all I can say in general. I am 2nd division officer in charge of the deck and gunnery division, with 70 men to look after with the assistance of two junior officers. Recently, I qualified as Officer of the Deck in full charge of the ship subject only to the Captain. These duties include directing the helmsman, checking the signals, decoding transmissions, knowing the latest technical data, and in general being in charge of the organization and maneuvering of the ship. Aircraft activities and the movement of other ships add to the excitement. It is the toughest watch aboard, and one where you catch the most hell, but offsetting that is the satisfaction in running the show for a few hours each day and night.”

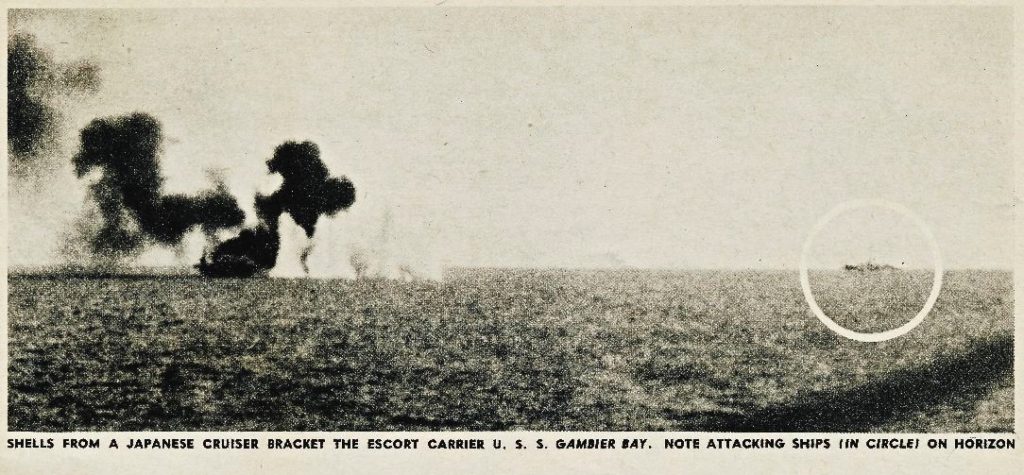

Shortly after sunrise on October 25th, Admiral Kurita’s Center Force of battleships and heavy cruisers launched a surprise attack on the outgunned smaller ships of Taffy III task unit in the epic Battle off Samar, one of the greatest mismatches in naval history. Under intense bombardment, the Gambier Bay capsized at 9:07 and became the only US Navy aircraft carrier sunk by surface naval gunfire in WWII.

Lt. Young and approximately 700 of his 950 shipmates were finally rescued before dawn on October 27, 1944. Prior to returning to the United States many weeks later, my father wrote his personal recollections of the devastating attack by Admiral Kurita’s battleships and cruisers, the sudden sinking of the carrier and the 43 hours floating with his men in the ocean, fighting off sharks and hallucinations while trying to survive on minimal food and no drinking water.

Young finally arrived back in San Francisco with the other rescued seamen in time to call his wife, Ruth Baum Young, on December 2nd which happened to be her birthday. He had written his dramatic narrative for publication in TIME Magazine, however, by the time he had returned other versions of the events had already been in print. Coincidentally, on July 24, 1944, TIME had published the photo below of a Japanese bomber being shot down by the Gambier Bay’s Gunnery Division under the direction of Lt. Young during the battle off Saipan.

The following account was written by my father in 1944 after his rescue.

Respectfully,

Philip Young

young23@me.com

Japanese bomber downed by by Gambier Bay

* * *

Lt. Robert G. Young’s Gambier Bay Story

We had never thought of her as anything but what she was – the Gambier Bay, an escort carrier with too little speed and too few guns. Now she was less than that, and more. She was a slattern, her face pulled down to the quicksand of blue sea and only her wet, mottled red pants showing. She was fat and undignified and upside down in her death sprawl, but as her rusty flanks were gradually lost in water we remember only the loveliness of her bosom and the gentility of her manners.

We had never thought of her as anything but what she was – the Gambier Bay, an escort carrier with too little speed and too few guns. Now she was less than that, and more. She was a slattern, her face pulled down to the quicksand of blue sea and only her wet, mottled red pants showing. She was fat and undignified and upside down in her death sprawl, but as her rusty flanks were gradually lost in water we remember only the loveliness of her bosom and the gentility of her manners.

The lady died on October 25, off the Gulf of Leyte, out of sight of the beachheads where MacArthur’s few divisions had put ashore; out of sight of any Philippine land. She went down with 20 ragged wounds and not many dead. To my knowing only one of her crew of hundreds went with her alive, a man so frozen by the moment that he never gave up his grip upon her rail.

She was my ship and in three hours she proved me wrong. I had not thought that she would ever die. I had said to Ensign Murray Sacks of Chicago, the recognition officer, “I have a feeling that this ship just can’t get it. I just have that feeling.”

“That’s right” he said. “I have that feeling myself. It’s a hunch I’ve got.”

We were both lying a little, but not much. I was almost sure my ship would somehow come through all right. She had rocketed airplanes at Saipan, at Tinian, Guam and Palau. She made kills with planes and guns and she had dodged bombs herself. But this was the Philippines.

I heard the voice that morning as I passed the radio room on the way to breakfast in the pre–dawn dark. It said excitedly, “The Japs are below me — four battleships, six cruisers and four destroyers.” Whose voice was this, and where from? The answers came quickly. It was the voice of a pilot from a neighboring carrier formation. By deduction he could be no more than 100 miles away, or anywhere within that radius.

The wardroom was crowded with officers and choked with buzzing conversations. A few lucky ones had drunk their tomato juice and coffee before the squawk box came on and Air Combat Intelligence Officer; Lieutenant Richard Elliott of West Hartford, Connecticut, said, “A strong Jap task force of 4BBs, 6CAs and 4DDs is 25 miles astern of us and closing.” The wardroom roared. When “Flight Quarters” sounded, the pilots rose as one man with a shout and poured from the room.

General quarters clang and the ship was instantly veined with snakelike files of men running to battle stations. I made my way to the bridge and joined the rush for steel helmets, talker phones and binoculars. I was to man a telephone that controlled the 40 MM batteries. The batteries reported manned and ready and I relayed that information to the gunnery officer.

This, we knew, was no routine drill. To the south, hidden by thick weather, was a powerful section of the Nip Navy. It was pursuing us and we were not so powerful. We were six escort carriers–freighters with flight decks–and three destroyers and four destroyer escorts.

Suddenly geysers of water were splashing up inside our formation in salvos of two to four shells. Through the rainy mist we could see flashes of red pricking the storm clouds astern. The battleships and cruisers had opened fire from about eighteen miles. We were under attack. It was difficult to grasp and feel the danger. The six carriers were leaving swirling white wakes as they turned in unison. Their decks were discharging bombing and fighter planes as fast as the handling crews could line them up for catapulting or flying off.

The noise of all the plane motors was deafening, but encouraging. These aircrews had carried our hopes before, but we knew the risk that lay in the formidable fire to which they were going. Each man cheered and prayed silently for them.

But if the airborne gallants stirred us, our tiny service escorts sent great lumps into our throats. For those fragile whippets had turned into the Japanese Goliaths and were throwing themselves across our sterns trailing great black banners of protective smoke. They had accepted overwhelming odds to shield us.

Nothing in the scene was static. Every ship in every plane moved. Even the sky was in motion. Clouds and rain squalls raced by, alternately blacking out and revealing the enemy forces. Chaplain Carlsen stood near me giving a play-by-play description of the actions of the men below decks over the public address system.

“Chaplain”, I said, “pray for more rain.”

He smiled and nodded.

The enemy was within 14 miles now, and the gunfire was becoming more visible, more intense, and more accurate. The rain passed and a panorama of Jap ships burst into excellent visibility. They seemed to surround us. But just as this crushing picture was shaping we spotted three ships hull down on our port bow, about 15 miles away and apparently approaching. One of the talkers on the bridge announced that they were three American cruisers. The Chaplain passed the cheering news to the deck hands below and we on the bridge passed it to the gun crews. We saw ourselves between two converging forces, a Hollywood finish to a series thriller in which we were to be snatched from disaster at the hands of the Jap fleet.

And about time it was! The shelling had become violent. The projectiles were clearly visible and we could hear them pass with a whoosh. They made brilliant spouts of colored water where they hit and they stalked the ship, creeping after it as change after change of course left thwarted misses where the ship might have been, but for the last maneuver.

Our five inch gun on the fantail opened up as the Japs moved into range. We never expected to be dueling against 14 inch guns with this weapon, but there was a satisfaction in hitting back. It was good to see the flash and smoke of our own fire. From the bridge we thought we could detect hits on Jap battleships, but the enemy moved closer and closer.

The gun crews sent anxious questions over the phone. Where were those American cruisers? We answered doubtfully. Identity was difficult at that distance. The signal bridge had challenged and been properly answered, yet the ships were not friendly in their movements. Some lookouts claim they were firing on us. We never knew who they were. They came no closer.

At 0645 we had seen the first flashes; at 0715 we took the first hits. The ship gave a shudder as a salvo of heavy shells landed in the middle of the after elevator at flight deck level. The flaming deck was quickly extinguished by well-trained firefighting squads. Each burst that shook the ship caused phone calls from every section, reporting wounded and asking for medical aid. As the requests became more numerous, we were forced to tell each battery it was up to them to dress their own wounded or carry them to first aid stations, since the bridge personnel were all busy with their own duties and problems.

The Gambier Bay was to windward of the formation, and the most vulnerable target, since our smokescreen blanketed the other carriers. Suddenly she gave a violent shudder, as though she had been mortally struck.

“The forward engine room is hit and water is rising,” announced the bridge squawk box.

Our position was becoming more untenable and we could not withdraw, strategically or otherwise. As the shells were spread all around us I shouted to Ensign Sacks•, “I wish there were a foxhole to dive into.”

“This looks like it”, he called back.

The MC speaker said “Air defense from after engine room–the forward engine room is flooded and the boilers have been secured” — a helluva word, which meant the fires were out and our speed cut in half. Not a man but felt the ship was doomed, although no one expressed such sentiments.

Our best defense had been to run and outmaneuver the enemy guns, but now we were running on one leg. This not only allowed the pursuing fleet to overtake us more rapidly, but also caused us to lag behind our formation. The Gambier Bay was the loneliest ship in the world. The closest Jap cruiser was now almost on our port beam and not over 3000 yards away. We could’ve hit her with our 40 MMs, but Captain Vieweg wisely did not give the order to fire. Our shelling probably would’ve killed some Jap personnel, but their retaliation would have cleaned out rows of our gun crews.

Only a few saw Lieutenant Cole Williams, the signal officer, throw weighted canvas bags overboard. In them were written matter and secret material. Those who did see him knew what that meant. The order was given to flood the magazines.

At 0840 we were dead in the water. At 0842 Lieutenant Warren Stringer, the gunnery officer, swung from the captain and out of his pale, agitated face came, “Abandon ship, abandon ship.”

Into my head phones I repeated, “Abandon ship, abandon ship.”

Automatically we tossed off our helmets and headphones. We had a sense of shame, as though we were deserting our posts. Up and till this moment we had been held by the regulating discipline of our immediate duties, for which we had trained endlessly. Now the spell was broken.

I was in the water; there were hundreds of us in the water. The shell which had struck the pilot house had neither hastened nor halted our scrambling down the monkey lines and dropping to the water. After surfacing, I kicked, swam as best I could with heavy shoes and clothing on. The many struggling figures on all sides were holding their own and no one was crying for help.

All were fighting to keep clear of the screws, which we did not know had ceased turning. I concentrated on staying afloat and trying, unsuccessfully, to inflate my life preserver. I drifted under the gun galleries, from which bodies came hurtling forty feet from the catwalk. Having avoided being struck by a shell, I had no desire to be stove in by a pair of Navy issue shoes.

The current took us by the fantail and I began to breathe easier. There were several rafts in the vicinity, many fully loaded. One went by with only Electrician Reed in the stern. He had on his glasses, with a pipe in his mouth, and as he nonchalantly paddled by shouted:

“Ferry to Hoboken, 15 cents; Jersey City 20 cents.”

A red geyser of water rose from a loaded raft, and bodies were hurled in all directions. A Jap salvo struck.

I reached the nearest raft with my last stroke, inflated with a quart of salt water inside me and with little desire to live. Seaman Elledge held my head out of water until the nausea had passed.

Everyone was making an excited effort to paddle and kick away from the ship. To remain near her exposed us to the hazards of shelling, possible burning oil or gas, explosions of ammunition or gasoline within the ship, or suction when she went down.

She was listing badly to port now. Some ammunition, probably 40MM, was popping and flashing. As she disappeared, a cheer rose from the next group of rafts–a tribute to the only carrier ever sunk by surface shell fire.

Now we focused our attention on our new home. The raft, a poor name for a partly submerged piece of donut shaped balsa wood, was in a very unstable condition. Supported by lines from its 8 feet by 5 feet sides, was a light wood mesh bottom, to which were lashed canvas covered tins of rations, paddles, medicines and water beakers.

Such a raft was designed to keep 25 persons afloat, but the whole affair was always a foot or two under water. This particular raft did not live up to the minimum requirements, for it had been a victim of shell fire. One end had been blown off and the bottom was riding free inside the doughnut hole; the ration tins were bobbing about and had to be constantly herded to keep them from drifting off.

Our situation was complicated further by the necessity of endeavoring to keep the several injured as much out of water as possible. Many of them had nasty wounds and were suffering silently.

Ray, the hospital corpsman in our group, swam from raft to raft procuring and administering sulfanilamide and morphine.

We were reminded of the ship’s presence by frequent underwater explosions, probably caused by depth charges which she had carried. No one was injured by these, but they made us feel squeamish and we continued in our efforts to paddle out of the area.

The sounds of battle have moved on, but units of the Jap fleet were perilously close. We were in danger of either being run down or fired upon. One destroyer charged past only a couple of brassie shots from us. We could clearly see the rising sun flowing from the mast, and at that distance she loomed as big as a battleship. After she had passed we breathed easier and Seaman John Zink of Tacoma, Washington, said: “Thank God those yellow bellies were nearsighted.”

Most of the struggling survivors had succeeded in attaching themselves to rafts, and many of the rafts were forming into groups. We had lashed ours to three others. The advantages of thus teaming up were many. We could pool our resources of rations, medicines and knowledge; the increased numbers buoyed our spirits; and perhaps, most of all, our larger formation could be more easily spotted and rescued.

“Let’s get the hell out of here” shouted Coxwain John Dunn.

Where he pointed were three Jap warships – battleship, cruiser and destroyer – only four or five miles away. They were not moving from the area and our helpless flotilla seemed to be drifting toward them. Having been spared the fate of going down with our ship, we did not intend to be shot at or captured by the enemy. Our paddling and splashing did not take us away from the menace, but the distance did not appear to be closing.

The Jap battleship was dead in the water and drifting at the same rate as we. The cruiser and destroyer were standing by to defend her. Rescue would be unlikely in the face of such a formidable force.

Tourist folders depicting the placid blue Pacific had deceived us. Gray waves of ominous height kept breaking over us and frequent showers drenched our heads and shoulders.

“Who are those two jokers,” said Kenneth Murray, pointing to an odd-shaped craft bearing down on us.

“Could be Mrs. Roosevelt or some native coconut salesman,” suggested Augustus Sanky. When the skiff came nearer it proved to be a large tarpaulin propelled by two of our steward’s mates, following an uncharted course toward land.

After a few hours, one of the officers in our raft flotilla who had been badly cut up by shrapnel, passed away. The pharmacist’s mate pronounced him dead. We gave him an hour and freed him from the raft, reciting the Lord’s Payer in unison as a burial ceremony.

A cheer went up at the sight of our planes closing in. Surely, they had spotted us and rescue would follow. But no, they had more urgent business. They formed two groups – high flying Dauntless dive bombers and an equal number of Avenger torpedo bombers. The dive bombers peeled off and in succession made vertical dives. Then the Avengers glided down in a low torpedo run. We had wet bleachers for witnessing the attack on those three Jap warships.

Smoke rose from the battleship indicating that she, at least, had been hit. But was misery to see one of our planes burst into flames and hit the water.

Darkness was approaching and we began to anticipate a night adrift. To consolidate our position we maneuvered our rafts and lashed to another group with the gunnery officer in charge. Several of us shifted to other less crowded rafts to equalize the load. We tucked ourselves in for the night with salt water. When the sun set, the wind subsided somewhat; but the high rollers were to plague us all night.

It was one long nightmare of people pushing together to keep warm, crowding to find a space to hang on to the raft, nodding to sleep and being wakened by a mouthfuls of salt water.

The morning light answered the question uppermost in our minds – are the Jap ships still with us? Not a ship could be seen, and Machinist Platner said: “During the night there was a burst of fire and smoke in the vicinity of the ships so maybe they scuttled the battleship and left in the cruiser and destroyer.”

Taking stock of our situation, we found that the rafts needed repairs. Lieutenant Commander Saunders, engineering officer, of Brooklyn, ordered all but the wounded off the rafts while repairs were being made. Most of the mesh bottoms had been kicked out during the night and ration cans were not secured. The bungs had sprung in all the water casks which meant no drinking water. The can of rations, however, was in water-tight condition. We had several tins of hardtack, malted milk tablets and canned meat. We doled out two tablets and a biscuit to each man. The limited medical stores were also waterproofed. Sick call was held and the above-water wounds treated. We found a yellow canvas which we spread to provide shade and to attract the attention of any planes.

Some of the rafts had drifted apart, but there were still five of them left and these we lashed firmly together. To relieve the crowded conditions, we established a rotating watch schedule which permitted one-third of the men to hang onto the raft for one hour at a time.

We were now ready for the day’s vigil of watching and waiting for friendly ships or planes. Lookouts were posted but everyone served in that capacity.

Eagle-eyed Vernon Schiffer of Tacomas, Washington, cried out: “There’s a submarine.” Next a destroyer was spotted. But whether the reports were true or false no help came within range. Two high flying planes passed overhead. We waved our canvas, fired hand rockets, and tried signaling with a shiny can top. No luck.

We saw two groups of rafts about a mile astern of us. A rubber life raft approached from their direction. It was manned by two masked figures, one of whom we identified as Lieutenant Commander Ximo Waring, the Air Operations officer. He said: “You are drifting in a one-knot current which will carry you into Leyte Gulf and to land, friendly or otherwise. We’re going ahead and should reach Leyte by 8 p.m. And we’ll send you a boat to pick you up by nine.” Belief in this piece of fantasy boosted morale for some hours.

By late afternoon conditions on the rafts had become precarious. The sun had been beating down on our bare heads and shoulders, the water was chilling the rest of our bodies, and the lack of water was beginning to tell on some. The wounded particularly were suffering. One whose face was torn open from shrapnel swam over and said: “I want to go below decks and turn off the leaking valves.”

Some were trying to attach an invisible motor to our convoy, A few became violent and had to be given morphine.

Ensign Lawrence Epping of Mt. Angel, Oregon, called me aside and pointed below us. Down 15 feet were several monster sharks, shadowing us. I had always fancied that the fear of sharks would be worse than the thought of drowning. Strangely, that wasn’t the case. No one became panicky at sight of them. A few violent kicks kept them at a safe distance.

Had we known that one of our shipmates who was swimming in white scivvies had been attacked and killed by a shark, we would not have been so nonchalant. A lone courier came bobbing along in the current and brought the sad tidings that Lieutenant Vereen Bell had died on a neighboring raft. He passed away with words of love for his wife and children. Now there would be no sequel to “Swamp Water”.

The current was full of surprises. We dispatched floating beach combers who returned with such booty as flight deck planks, airplane tires and a wooden walkway from the open bridge. The hobby lobbyists aboard improvised an observation platform in the stern sheets.

I stood up on one end of our flotilla to have a look around. What a gruesome sight we made. Every raft had its wounded, many with bloody bandages. The yellow canvas stretched on the paddles afforded some protection from the sun, but gave the appearance of a nondescript houseboat. Even the uninjured looked formidable after thirty-five hours of exposure and without shaving. We looked like a pirate band which had received the worst of a scrap.

The sun was dropping low in the sky and still no sign of land or rescuers. We gave each man another share of biscuits, tablets and meat. With the only knife aboard, I carved and felt like a mother bird inserting the scraps into the outstretched hands. Mealtime was quite a ceremony. It was the only scheduled event of the day; so we dragged it out as long as possible, taking unusual care to keep the food out of water and to cut the meat in identical shares. After dinner, Lieutenant Stringer led us in silent prayer for our deliverance. This spiritual and physical nourishment made us all feel better.

We were still drifting steadily toward land, we hoped. Some paddled, but this helped their morale more than our progress. The night dragged on to what seemed like a worse dose of misery than our previous one.

Everyone was getting more irritable. Our flesh had become soft and pulpy from immersion, and digs from others’ feet brought forth cries of “Stop kicking me”. Men were falling asleep and a few drifted away. Some swam into the blackness to other rafts to escape the feeling of being chained.

At last a comet brightened the sky ahead; then another. They were flares. Help was on the way. We hurriedly dug out our Very pistols and fired three flares at intervals. More colored streamers answered our signal.

“Everyone yell,” A shout came from the darkness. And everybody did yell, in spite of the distance.

“Shut up, they might be Japs”, from another voice.

“To hell with the Japs” – and the shouting continued.

A searchlight came on, still miles away – like a truck winding down a long hill. We were a cluster of refugees on a train platform as the L.C.I. troopship picked us up with her light and steamed slowly alongside. The wounded were hoisted aboard first, many by stretcher. I was able to navigate, but like many others climbed the ladder with wobbly legs which gave out on reaching the deck.

Helping hands steadied us and led us below. In the tiny wardroom were the six officers who had been on the rafts. We drank sparingly of coffee and water. The chronometer on the bulkhead registered 0330 or 43 hours in the sea.

“When does the next boat leave for town?” I questioned. My mind was beginning to wander. We stretched out on bunks or on the deck. To lie down full length and not feel the water chilling and lapping at us was heaven!

I awoke to the sound of AA gunfire and peered through a porthole in time to see a Jap Betty bomber zooming away. Dangers held no fascination and I retreated into unconscious.

Robert crossed the bar in February 1991